Penzance Sea-fishing Boats

21 July 2019Pz.28 Ada

27 August 2019A visit to the north-west of County Clare allows one to look further into Walter Hunkin’s narrative. As one might expect of a former ship’s captain, he turns out to be precise in his measurements which reinforces the belief that his is a fair account of his past.

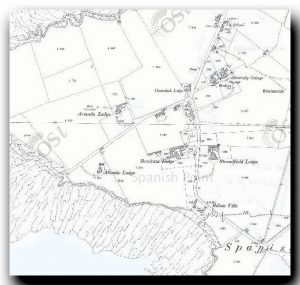

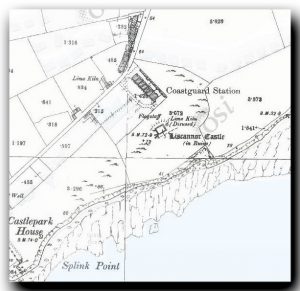

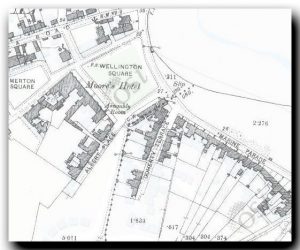

Fortunately, the excellent Geohive mapping site has an overlay of the 1888-1912 25 inch OS map which shows some of the historic buildings and enables one to pin down some of the buildings which Walter would have known.

His journal gives us a few hints about his life ashore, following his arrival in County Clare in 1906. He mentions that he was initially responsible for four stations ‘one having been recently closed – and one war signal station not manned in peacetime’. From what follows, we can identify Liscannor, Seafield and Kilkee. The fourth and the closed station are not named.

Later, he refers to Loop Head as being the ‘War Signal Station’ and its prominence in his account increases once WWI gets under way: the Coastguards’ priorities had clearly changed with the arrival of war.

Spanish Point

It seems that a house was provided for him at Spanish Point, ‘a rocky stretch of coast where a landing was never attempted’. He was unimpressed, describing the house as ‘a rambling old property belonging to the Admiralty that had been enlarged from time to time.’ There were at Spanish Point ‘a few houses, closed in the winter and opened up for the use of visitors during the summer.’

Enquiring about the location of the Coastguard Station he was told ‘The station is beyond, at Seafield Point’ as the driver pointed ‘to the station buildings, visible across the bay three miles distant.’

Today (2019), ‘Spanish Point’ is a sweeping bay of sand, inland from the point itself, with a series of typical seaside houses, apartment blocks and a hotel lining the head of the beach. No doubt many of them still fulfil Walter’s description of being closed in winter and open for the use of visitors in summer. Few of them look old enough to have existed in Walter’s day although there are some small, traditional-looking bungalows of a typical four room Irish model.

The red house on Spanish Point. 2019 Could this be the house offered to Walter Hunkin?

Geohive shows a complex of buildings at Spanish Point, several of which are possible candidates: Admiralty Cottage, complete with flagstaff, Cavendish Lodge, Armada Lodge and Atlantic Lodge. These exist in much adapted form today.

Our preferred candidate was Atlantic Lodge, a large red house which looks of the right period to be the house he was offered. A back extension suggests that it could fit his description as having been ‘extended’. Importantly, it is the only large house which has clear sight of Seafield Point which is indeed 3.3 miles (5.3km) across the bay. It therefore seems a good candidate for the house he spurned.

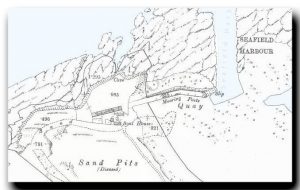

Seafield Point

Seafield Point is a remote spot at the end of a long curving beach approached from the village of Quilty. Walter describes it as being ‘2 miles from Quilty railway station bordering on a road leading along the shore’ and ‘sixteen from Kilkee’ (it is indeed sixteen).

At the Point, a low headland of rock and grass-covered dunes, is a small historic jetty built of stone which has been recently enlarged with a new concrete wharf. The original jetty would have provided a degree of shelter for half a dozen small boats which would have been aground at low tide.

Seafield Point jetty 2019, looking north-east towards Spanish Point

Shown on the historic map is a long W-E building facing a small ‘boat house’. The remains of that low building remain in the form of a single-storeyed bungalow with outhouse. the ‘boat house’ has disappeared.

Seafield Point 2019: the remains of the long low building. Was this once the harbour office?

The historic map shows the Coastguard cottages themselves, which Walter describes as having been ‘erected at the time of the Fenian movement [and which] were very well and strongly built with a view to resisting attack during any possible raid on the station. At one end of the buildings there was a strongly built tower protected with heavy iron shutters at the windows and loopholes – very like the castles of old – for rifle sniping of any persons leading an assault on the station. In each house there were iron communication doors leading from house to house, by which means the crews, with their wives and children could, if necessary, reach the strong room in the tower, close the communication doors and await events.’

Seafield Point 2019: the elusive buildings which bear the hallmarks of Coastguard cottages

These were some way from the quay and no trace remains on the ground today.

Tantalisingly, halfway between the point and Quilty, bordering the road is the remains of a stone-built building which bear all the hallmarks of being a row of Coastguard cottages with individual doors and windows. A block at one end might possibly have been a small tower. These are shown on the historic map but with no indication of their purpose.

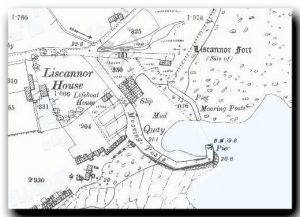

Liscannor

Walter also mentions the Coastguard station of Liscannor which, he says, is ‘thirty miles distant’: presumably from his home at Kilkee. It is in fact 28 miles by road today.

Walter also mentions the Coastguard station of Liscannor which, he says, is ‘thirty miles distant’: presumably from his home at Kilkee. It is in fact 28 miles by road today.

‘Arriving at Lahinch railway station …’ which is no more ‘… one drove around Liscannor Bay, past Lahinch golf course, a long stretch of sand hills said to be the best golf course in the country …’ The golf course still exists – indeed there are now two – and still consists of sand hills. It hosted the All-Ireland Golf championship in 2019.

‘… passing the ruins of an old chapel which probably fell into disuse during the penal days.’ Entering Liscannor, one passes the ruins of Kilmacrehy church.

Liscannor harbour 2019

A short distance further on is the small harbour of Liscannor which is an altogether better refuge for small boats than Seafield Point 10 miles further down the coast.

At the head of the slipway is a small stone building called ‘The Old Coastguard Boat House’. This is of a design which is very similar to that of Newlyn in Cornwall built shortly after 1902. It is marked on the historic map as ‘Lifeboat house’ although local signs call it the ‘Old Coastguard House’.

Liscannor harbour 2019: the ‘Old Coastguard Boat House’

He goes on ‘Within the grounds of Liscannor station there stood the ruins of a very fine commodious old castle’ which, from his description, sounded intact.

The castle is very far from intact today.

Liscannor castle/tower house 2019

The original Coastguard house has completely disappeared, and a school stands in what was its garden.

Other features

St Brigid’s Well 2019: the entrance to the well

Walter mentions St Brigid’s Well, which he spells as ‘St Bridget’s’, ‘about a mile from the village of Liscannor.’ It is just over 1.5 miles as the crow flies and still exists as a shrine.

He also mentions the Cliffs of Moher ‘for which the Liscannor Coastguard Station was responsible’ … ‘the approach to which was over a very rough road with a steep uphill climb to the top of the cliffs 700 to 800 feet above sea level. These remarkable cliffs, well-known to all tourists of the county of Clare, are unsurpassable in their majestic grandeur, their wild and natural beauty.’ He goes on to mention the ‘teeming seabird life resting and nesting in the inaccessible ledges and crannies’ and reports on the visit of a friend.

The cliffs of Moher 2019

Today, the cliffs of Moher are reckoned to be Ireland’s ‘favourite tourist attraction’ with a visitor centre and thousands of people visit the new visitor centre each year. The seabirds still nest on the ledges and the 700 foot drop is still awe-inspiring. Thankfully the very rough road has been improved.

Interestingly, he does not mention the small village of Doolin which stands at the eastern end of the cliffs. Here there is a small pier from which vessels take trippers out to the nearby Aran Islands and it might have been natural to include it in his command given his responsibility for the cliffs.

Kilkee

Walter chose to live down the coast at Kilkee, taking a house in Albert Place. This still exists and a comparison of the original map and the modern one suggests that the houses have not changed their footprints.

Walter chose to live down the coast at Kilkee, taking a house in Albert Place. This still exists and a comparison of the original map and the modern one suggests that the houses have not changed their footprints.

Further work

There are hours of fun to be had searching the Geohive site and other Coastguard stations can be identified all around the coast.

What does seem strange, to this researcher, is that the two rows of cottages at Liscannor and Seafield were completely destroyed at some point between Walter’s time and the modern day. In a country where unwanted buildings are either re-purposed, pulled down and re-built on the same footings, or left to rot and/or plundered for building materials, it seems strange that there is no clear evidence of either group on the ground. Were they swept away after independence as evidence of the past?

JG/February 2020