The Years at Sea

2 October 2018Aboard the Squirrel on the Clyde station

13 October 2018Walter joined the Victoria with the rank of Leading Seaman, soon being promoted to Quartermaster and then Acting Petty Chief Officer. The Victoria was a first class yawl of 131 tons. The Limerick station covered the whole of the west coast of Ireland from a base at Tarbert in the mouth of the River Shannon.

I Become Permanent for Coast guard Cruiser Service

Within an hour or two we were underway with a list of coast guards for removal from one station to another with their families and effects. The railway facilities in the west of Ireland were not very convenient for this purpose. In many instances a coast guard station would be as much as forty miles distant from the nearest railway station; consequently practically all the removals were carried out by the cutters.

It would sometimes happen that a batch of new entries from the fleet for stations on the west coast would arrive at Queenstown on route to their appointed stations, accompanied by their wives and children and such effects as they had decided to bring with them. A cutter would be there to embark them and, as wind and weather permitted, would eventually land them at their station. Very often their changeover from the fleet to the coast guard service was anything but a pleasant introduction. For many of them on joining a coast guard station would mean ten, fifteen or even twenty year’s isolation at these backward stations, never being in a position to afford the passage money for a holiday in England. To get a removal to a station in England or Scotland would not be considered for ten years and, should it ever be granted, it was considered a great favour bestowed on the best behaved.

The Admiralty, in the interest of economy, always jibbed at the cost of removing men to England. On the other hand, it was quite common to send an officer or man from an English station to the west of Ireland for punishment. By this reasoning, surely it was a punishment to the man appointed to an Irish station in the first instance. Should an officer or man reach the age for his pension he would have to pay his own expenses to the place where he intended to settle. Such were the secrets of the coast guard service at that distant period.

The coast guard personnel had no knowledge or training in signals, nor was anyone on board the cutter able to make a signal by semaphore. On arriving at a station to embark a man, a flag would be hoisted from the coast guard boat to come off, when they were informed why we had come. In many instances the station would be many miles from the nearest telegraph office and sometimes the cutters would arrive at a station to remove a man and his family before the order had arrived at the station for his removal. There would be no time to lose, the opportunity of embarking in moderate weather and a smooth sea had to be taken advantage of. Sometimes a chance lost meant waiting for days or even weeks for another chance.

With the help of his mates, he packed up with all haste and with his wife, family and effects, bundled on board in the least possible time. The only landing place at some stations was a rock bound cove or an open beach and with the ocean swell it was not uncommon for the boats crew, the coast guard and his effects to come on board swamping wet. At the best of times this method of removal was always rough on women and children, but after getting them on board we always did our best for their comfort. I have known them to be on board anything from one day to four weeks. Once on board no-one could say when they would land again.

Under the most favourable conditions, this embarking and landing from the open stations was anything but a picnic either for the coast guards or the cutter’s crew. There was no real accommodation provided other than one small cabin, but usually the petty officer gave up his cabin to the second family taken on board and so on, and sometimes the commander would allow them the use of his cabin.

Very soon I settled down to the routine of my new ship and my new shipmates. The commander, a north of Ireland man, was a splendid west of Ireland pilot, a kindly good shipmate but a poor disciplinarian.

Up to that time I was not sure that any day I might be sent back to Devonport for general services. Now that I am a Leading Seaman and on the permanent list for the cruiser service I can look forward with a contented mind and hope of promotion in due course.

In March the ship was ordered to proceed to Devonport for general repairs. After the monotony of the west coast of Ireland, the prospect of spending a few months at Plymouth during the summer, and a possible few days leave, was a prospective pleasure not anticipated.

During the period of the repairs the crew were billeted on board the receiving ship Royal Adelaide, working daily in the dockyard on board our own ship.

For a few days I was deputed coxswain of the Royal Adelaide’s cutter, a twelve oared rowing boat. On one occasion, the boat being moored at the town boom, with a strong tide and fresh wind, I was experiencing some difficulty in getting from the boom into the boat when, who should appear at the gangway but the officer of the day, a salt house lieutenant. Very soon he was shouting his orders to me, not in the most select language, finally calling me a b** useless article. In silence one wondered which was really the useless article.

During our four month’s stay at Devonport I had the opportunity of spending several weekends at home, notwithstanding the fact that there were cases of smallpox in my home town. Had this been known to the authorities, it is not likely that I would have been allowed to go.

As the time passed and the day arrived for returning to the west coast of Ireland, I think that the crew, with the exception of the Irish men, all felt very sorry. However, we had all had a good time and enjoyed the change of a few weeks in harbour.

Laden with stores for distribution to coast guard stations, in August we set sail bound for our home district, and with the fair weather at this season of the year effected good landing right up the west coast, arriving at Lough Swilly about the tenth of September, where orders awaited us to proceed to Queenstown. On the fifteenth we sailed with a favourable breeze, making a good run south.

During the afternoon of the 17th of September the ship was running through the Blasket Sound, on the coast of Kerry, with a fair wind and a fresh breeze, under plain sail with the square sail set, it being my watch on deck. A man was sent aloft to a job at the mast head and for some unexplainable reason he lost his balance and fell striking the crosstrees, the boat and falling into the sea. Everyone was startled, both on deck and below, by the cry ‘man overboard’. With the instant thought that he would be drowned if left without help, I ran along the deck and plunged over the stern to his assistance. The Commander, at the same instant, threw over the lifebuoy. I first get hold of the lifebuoy then swam and got held of the man, pulled him over on his back with the lifebuoy under him, and holding him in that position bade him to keep quiet, assured him that he was all right, and that we would be picked up very soon.

On board of the vessel canvas was shortened in quick time, the vessel hove to, the boat lowered and manned by a willing crew straining at the oars was soon making towards us with all possible speed. They had not only to contend with the wind but also with the rapid tide running through the sound.

For the first few minutes the distance from the ship was forever lengthening. Then one saw the canvas lowered, the vessel hove to, then the boat in the water pulling towards us. It was a hard pull, were they making any progress? How long could I hold on? Would the boat reach us in time? And such like thoughts flashed across one’s mind as every five minutes felt like an hour. After twenty five minutes, to feel the saving grip of the chief petty officer on my shoulder and to see my injured shipmate – Daniel Kidney, a young Irishman from Whitegate – pulled into the boat was an experience not to be forgotten, and looking back through the years I regard it as the most delightful moment of my life.

After regaining the ship, the boat hoisted, we were underway again. Mr Greenham, the mate, applied first aid, found that the man’s leg was broken and his chest much bruised. He ordered the carpenter to make some splints and then he set and strapped the leg making the man as comfortable as possible. Putting into the first harbour, Valencia, the man was landed the same evening and taken to the cottage hospital where the doctor pronounced the leg to be well and truly set and only required to be re-bandaged. After three months in the hospital he re-joined the Victoria. Kidney, a nice quiet shipmate, was ever grateful for my help rendered that afternoon.

In October we were again back at Rathmullen – where the commander had his home – and there fell in with the parent ship. After a few days, orders were received that the Victoria was to proceed to the North Sea for fishing duties. Such a thing had never been heard of before, as a cruiser to be sent from her home station on the west of Ireland for duty in the North Sea!

On the receipt of this order the commander was very much disturbed. The majority of the ship’s company were rather pleased at the prospect of going across to England for a change. He did all he could to delay our departure and when, eventually we did sail, tried his best to carry away one of the spars, such as the main boom or gaff, by repeatedly allowing the mainsail to gybe over in a strong breeze, but nothing gave away. Eventually a small spar, the mizzen boom broke; now he had the desired excuse to go back to Rathmullen to report and obtain a new boom. This caused a further delay of a few days. At last, there being no more cards to play, we took our departure on passage for Harwich, calling at Blacksod Bay to embark a station officer for removal to Scilly Islands. The time was spun out by calling at various ports for no particular reason.

On the morning of our sailing from Blacksod, just after getting underway, when running down the bay with a fresh wind, the lookout man reported “Imogene in sight sir”. After a little while the ‘close’ signal was run up on board the Imogene and a couple of guns fired to attract our attention. Our commander took no notice knowing the district captain to be on board visiting his stations. Being at the helm, I saw him give a wink to the petty officer and heard the order to set more sail. The square sail was soon set and with the fresh wind, the Imogene, a slow steamer, was soon out of sight; probably our commander chuckling to himself that he had done the ‘old man’ that time.

In crossing the channel, on sighting Scilly it was found we were some miles to leeward, consequently the vessel had to be hauled close to the wind in order to round the Seven Stones. The sea being very high, we had a most lively time for three hours with as much water sweeping the decks as one could ask for.

On arrival, and taking up a berth in the usual anchorage, the first job was to land the passenger and his effects and after a hard pull against wind and tide he was dumped ashore on the rocks, no doubt glad once more to have the solid ground under his feet after the discomfort afforded on board of a coast guard cutter. There we remained weather-bound, rolling and tumbling about in St Mary Roads for a week. With the weather moderating we proceeded on our passage, calling at Devonport to land condemned stores etc., remaining there two days then sailing for our destination at Harwich.

North Sea Fisheries duties

As we proceeded up Channel the wind drew down from the eastward bringing a large fleet of sailing craft that had been wind bound in The Downs, running down with a fair wind while we were turning to windward back and tack. The night was pitch dark and to fall in with so many craft was rather perplexing to the Commander who, on the west of Ireland, would not sight a sail in a month. About the middle of November we arrived at Harwich, where orders awaited us to proceed to sea on fishery protection duty with the herring fleet working from Yarmouth and Lowestoft.

Our commander, a most capable west of Ireland pilot, had no experience of the east coat of England, and was unacquainted with the dangerous banks and tides and unaccustomed to the company of hundreds of fishing craft and the numerous quantity of shipping forever passing and repassing. It was all very perplexing for him; consequently he had to fall back on an extra dose of his favourite tonic to keep his heart up.

By this date the herring fishery was drawing to a close. After one month, by the middle of December, the fishing fleet had withdrawn and the fishing cruisers were ordered to return to their respective districts. This, my first experience of North Sea fisheries protection was by no means the last.

No time was lost by our Commander in getting away. On or about the twentieth of December we sailed from Harwich making a good run down channel and arrived at Queenstown on the 24th of December. The first thing was to land the caterers, to obtain some extra Xmas fare. The Xmas pudding was made and cooked during the night in preparation for the Xmas feast, provided out of our own pockets.

Xmas day was free and easy, everyone doing his best to make the other happy. The Xmas festivities now finished on the 27th, we were underway again, bound up the west coast and arrived at Bantry on the 28th December 1885. With the opening of the New Year 1886 we were in company with the parent ship in Bantry harbour.

At the end of every year a report of every man’s character and ability was rendered to the district captain for the Admiralty records. Against my name for the year closing 31st December 1885, my commander had noted ‘recommended for saving life’. When the report was laid before the captain by his secretary, he, not having heard of the incident afore mentioned, demanded an explanation. It was found that the report forwarded in September had been pigeon-holed. Our commander was ordered to appear on board where he found the captain making things rather lively for the office staff until the missing report was found.

Then a signal came over: ‘send Hunkin on board’. In due course I appeared on the quarter deck. The district captain commended me for my action in saving the life of a shipmate, expressed his regret that the incident had not been brought to his notice earlier and that he would lay it before the Admiral without further delay, after which I was dismissed and returned to my own ship.

1886 – Back on the Irish station

After a few days we sailed once again on passage to Rathmullen carrying out a few removals en route. There was one removal from Dingle to Achilbeg. It was the middle of January, a bad time of the year for landing at any of the exposed stations. Arriving at Achilbeg I suppose the commander wished to get to his home as soon as possible, although the prospects of landing this man and his effects were not very good. The two boats were lowered and loaded with the man, his wife and children and goods. The first boat put off and on nearing the landing place it was seen that the sea was rather rough on the shore. The petty officer in the boat hesitated but finally made the attempt to land; on reaching the beach he thought to get the gear ashore all right but, before the last packages were out, a sea more weighty than before filled the boat swamping men and gear. With the help of the coast guard and other willing helpers the boat was freed from water and eventually came back, the men none the worse for having got a wet shirt. It was all in the day’s work.

On arrival at Rathmullen 14 days leave was granted to each watch. My leave came with the second watch, making the best of my way home in company with two others going to Plymouth. In due course I reached home and spent my all too short leave comfortably with my friends.

Going to London for a few days I must confess, at the expiration of my leave that for once and the only time I deliberately overstayed my leave by one day. When I arrived back in Rathmullen in the evening, I found that the vessel had left the anchorage that morning for sea. Happily for me there was very little wind and the Victoria had to anchor a mile or so down the Lough. The Stag, a sister ship being at anchor, I reported myself on board and the officer in charge manned a boat and sent me on board my own ship. Of course I was very delighted not to be left behind. My kind hearted Irish commander, who disliked punishing people, did not even reprimand me but presumed that I had missed the train.

The busy season for carrying out removals was close at hand and for several months we were employed up and down the west coast removing coast guards and their families, collecting old stores and the coast guard men for passage to the district ship for the annual summer cruise.

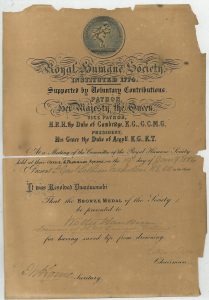

On the first of April 1886 I was promoted to petty officer, remaining in the same ship. This promotion was awarded me over five other leading seamen my senior, as a reward for the act of life saving. In due course I was awarded the bronze medal of the Royal Humane Society. The district captain, wishing to make the presentation of the medal himself on board the Shannon, retained it for a time but we were so many months absent from the parent ship that the medal was sent on and presented to me on board of my own ship in presence of the ship’s company.

On the first of April 1886 I was promoted to petty officer, remaining in the same ship. This promotion was awarded me over five other leading seamen my senior, as a reward for the act of life saving. In due course I was awarded the bronze medal of the Royal Humane Society. The district captain, wishing to make the presentation of the medal himself on board the Shannon, retained it for a time but we were so many months absent from the parent ship that the medal was sent on and presented to me on board of my own ship in presence of the ship’s company.

In October we were at Rathmullen in company with the district ship. The other tenders arrived, including the Fly. The annual inspection was carried out by the captain. Our commander left us for a better command, taking charge of a steam cruiser stationed on the English coast.

My old shipmate, the commander of the Fly, usually known by the pet name of Jimmy, was transferred to the command of the Victoria. In due course sailing orders were received and preparations made for getting underway at four a.m., scarcely daylight at that season of the year. On raising the anchor, there being a fresh breeze, unfortunately we fell afoul of the Fly, carrying away her bowsprit and other damage. Jimmy did not come on board until midnight, so possibly his vision was not very clear at four a.m. No damage was received by the Victoria and disregarding the recall signal from the senior officer, proceeded to sea.

Our first port of call was Killybegs where, on arrival, orders were received to return to Rathmullen. Jimmy’s home being at Killybegs, he hung on there for a few days. On the day of sailing the weather was fine with a moderate breeze from the south west. It being my afternoon watch, I was left in charge of the deck, waiting out of the bay and reaching in rather close to the cliff, I experienced a very nasty few minutes. The vessel narrowly missed stays – that is she was sluggish in answering the helm and coming around on the other tack. Had she failed to come around I could see her thrown up on the rocks and my career finished. The man himself was below, probably bracing himself for the ordeal that awaited him.

It being my first watch, I relieved the deck at eight p.m. By eleven o’clock the wind was freshening, veering to the north-west and weather threatening. At midnight the watch was relieved and very soon after the officer of the watch could be heard shouting his orders to shorten sail. The vessel was snagged down to close reefs in the canvas and preparations made for stormy weather. By four a.m. we were a few miles to the westward of Tory Island. The wind still freshening flew to the north coast, increasing to a strong gale with a high sea. The mate now in charge of the deck decided that there was no alternative but to heave to and ride out the storm.

The gale raged with unabated fury all that day and night. The forenoon following, it being my watch, about ten o’clock, a heavy curling sea broke on board, breaking the stanchions, carrying away the bulwarks on the starboard side and splitting the mainsail. Even this failed to bring the gallant Jimmy on deck. On the third day the storm moderated and under the skilful navigation of himself – who had not left his cabin since leaving harbour – we arrived at Rathmullen somewhat battered by the storm. A court of enquiry into the collision with the Fly was held on board of the district ship and the finding of the court as is usual forwarded to the admiral.

In due course the Victoria and Fly were ordered to Londonderry to make good damages. After a few weeks a word came that Jimmy was to be suspended and to work to the command of a small cutter stationed on the south coast of England. That was punishment enough, seeing the Victoria was the very vessel he most desired to command.

For many weeks we remained in Londonderry extending over the Xmas, and for some unknown reason no Xmas leave was granted. It almost appeared that it was a punishment of the ship’s company on account of the offence of one. During our stay, the anniversary of the siege of Londonderry and the locking of the gates by the apprentice boys on the seventh of December 1688 was celebrated by the decoration of the streets, processions by the Orangemen from the masons’ lodges, with an indulgence in merry making and feasting. All our men had the time of their lives, their ‘blue jackets’ gave them an entrance anywhere and a welcome on every hand.

1887

With the coming of the new year 1887, there was a heavy fall of snow and heavy frost; consequently, as is customary in Londonderry at these times, a great deal of winter sports were indulged in. The favourite game, tobogganing down that very steep incline, Ship Quay Street. Our men were always welcome to a run on anyone’s scooter or sleigh. The weeks passed pleasantly, all our men having had an enjoyable time and escaped some of the winter gales, the latter being appreciated by all hands.

In due course, another officer was appointed in command and Jimmy walked over the side.

In February we sailed with a long list of coast guards with their families for removal. The new commander had no experience of the west coast of Ireland and was consequently quite at a loss to decide whether it would be safe to attempt a landing or not, and being a bluffer, was forever in an indirect manner pumping the Mate and Petty Officers for information. He very soon discovered the difference in this work compared with the south coast of England.

Among these removals there was a man to be landed at Seafield on the coast of Clare and another to be taken off. This station, having such an extended rocky foreshore, a landing there was never attempted, but was done in the River Shannon and the men or stores sent across by road. The Commander would make the attempt, consequently one of the boats got holed on a sharp rock and nearly filled before reaching the shore. That caused delay and fault-finding when the boat returned. Of course someone had to be blamed for the stupidity of himself.

It was no uncommon occurrence dodging off a station for days, awaiting a chance of a smooth sea to land or take off a man and his family.

The Commander was very fond of the sporting gun and never missed a chance of a day’s shooting. Often he would land on one of the numerous islands and bring on board a bunch of rabbits, a very acceptable addition to our service allowance. Of course he must keep a dog or two and appeared to be all the time buying or exchanging dogs, generally having four or more – Irish setters, terriers, spaniels, pointers or mongrels. Personally, I detested those dogs, especially if one had to go into the cabin at night with a snappy terrier at the foot of the ladder.

Our favourite, the ship’s dog ‘Sailor’, a fine black retriever, resented the intrusion of these strangers very much. He was the pet of the crew. When turning to windward against a head wind and the watch below were stretched off on the lee lockers ‘Sailor’, who was always seasick in rough weather, when the ship was hove about on the other tack, would always be the first across and take up a comfortable billet. He was ever ready for a run ashore if anyone would take him. On one occasion, landing with the mail, I took the dog with me and crossing a field where there were a number of sheep, missing him from my side, I discovered ‘Sailor’ mauling one of the sheep. Luckily for me the farmer was not in sight. When the vessel was at Rathmullen, ‘Sailor’ would, when left on shore, instead of waiting for the boat, swim off, barking when nearing the vessel to call attention. The watchman dropping the bight of a rope over the side, the dog would get into it and so be hauled on board. If the ship should be swung to the ebb tide he would go well up the shore before taking the water, so that he would not be carried past the vessel and have to swim ashore again, taking the same precautions with a flood tide.

The early months of the year passed and early in June we embarked a number of coast guards, conveying them to Bantry to join the district ship for the annual cruise.

On the 21st of June, when the whole country was making merry on Queen Victoria’s jubilee day, we were carrying on as usual taking advantage of a smooth day to land a coast guard at Ballyheigue in Kerry, then proceeded to Galway to work under the orders of the divisional officer for a few weeks.

During this time, one of our seamen got a bit wrong in the head, rushing about the deck, beating his head against the bulwarks, etc., eventually jumping overboard. He was picked up and the medical officer ordered him to be sent to the naval hospital Queenstown. It fell to my lot to accompany him. On the journey we passed a mental home and seeing the inmates in the grounds, he remarked “those are my future shipmates”. His trouble turned out to be the result of a little love affair. He soon recovered and returned to us once again.

By the end of the summer cruise of the coast guard and reserve fleet we were at Bantry in readiness to embark a batch of coast guards for passage back to their stations. Once on board the cutter they had no idea when they would land. There was no bedding for them, the best we could provide was a sail and stretch out on the lower deck. What with foul winds, calms, or bad landing conditions, they would sometimes be on board as long as two weeks or more before the last of them were landed.

In September the vessel was deputed for fishing duties in Donegal Bay. After about six weeks, during which time the commander took every opportunity of landing for a day’s shooting and the crew amused themselves fishing for mackerel. The strange part of it was there were no fishing craft of any sort sighted in the bay.

With a few weeks on removals, in November we found ourselves at Bantry in company with the parent ship. Taking this opportunity I underwent an examination and passed for a chief petty officer.

Early in December two coast guards with their wives, families and effects and the furniture of a third man who preferred to pay his own fare to England, was embarked for conveyance across channel to Dartmouth and Portland; a cruel method of conveying women and children in the dead of the winter in such a small craft. Supposedly it was in the interest of economy; the country must have been poor and could not afford to send them another route. There was furniture and effects as much as could be stowed on deck and below, with two coast guards, their wives and twelve children.

From the Fastnet to the Longships we had a fair passage, with the wind about west north-west. Making the land about four p.m. with heavy rain and the wind falling light, there being a long December night ahead, sail was shortened to a single reef mainsail. The mate, having been promoted, had left the ship and we were without a mate this voyage. The commander was to keep the first watch and my middle watch. About eleven p.m., the wind freshening from north-east, in my bunk I could feel that the vessel was making bad weather of it and was being driven under too great a pressure of canvas. I called the Chief P.O. and told him I was going on deck to see what was taking place. Donning my oilskins and sea boots, I went on deck. The staysail had just been hauled down, thus easing the vessel a little. It was quite time that she was hove to and sail shortened. The commander with his Dutch courage kept her going, tearing through the water, the wind now at gale force.

As soon as I got on deck I went aft and remarked to the commander on the force of the wind. He ordered me forward to help in reefing the staysail. Within a few minutes – I had just cautioned the men to look out they were not washed overboard, the wind burst on us with hurricane force laying the vessel over on her beam ends, the water pouring down the skylights and hatchways in tons. Every one of the crew rushed on deck thinking the ship was going down, the chief petty officer shrieking with fright and the coast guards terrified knowing the danger to their wives and children. I found myself on the lee bow hanging on to the chain cable to prevent myself floating away over the lee sail.

Among the crew there was an able seaman that had been in the vessel several years. He, without orders, lowered away the mainsail by the throat halyards thus easing the vessel immediately. The helm was put hard a starboard. She came up head to wind and around on the starboard tack, with the deck full of water. To free the deck I unshipped the starboard gangway; it slipped from my hold and went overboard. An able seaman unshipped the port gangway – that also went overboard, the seaman narrowly escaping going overboard himself. The vessel was now safe and quiet, hove to, and sail was further shortened.

The commander very soon decided the vessel was heading toward the shore and must be brought around on the port tack. The wind was so strong and the sea so high that it was impossible to tack ship. The vessel was then wore around, kept away before the wind, and the mainsail allowed to gybe over from one side to the other, a dangerous manoeuvre in a gale with the risk of carrying away any of the spars. Fortunately no damage was done. In a very short time he updated the manoeuvre and came back to the starboard tack again. The crew were then mustered to find if anyone had gone overboard; happily they all answered their names.

To show the quantity of water that got below, it took three hours with our four inch Downton pump to free the bilges. A quantity of the furniture on deck, with loose ship’s fittings, was washed away and the boat stowed on deck stove in.

It is not for me to comment on the ability of himself, but I think the endangering of the vessel and neglect to shorten sail in time was probably due to the ‘poteen’ or, as Paddy would say, ‘mountain dew’ brought on board by one of the coast guards.

It being my middle watch, I had to carry on in my wet clothes as I came out of the water, just emptying the sea boots and pulling them on again. Such were some of the delights of service in small ships.

With approaching daylight and the gale moderating, the voyage was continued, anchoring in Falmouth harbour. Within the sheltered waters of the harbour the able seaman and myself were paraded on the quarter deck by our gallant officer – possessed with more bluff than brains – and charged with the offence of throwing the gangway pieces overboard. One might have attempted to defend oneself, but as I was looking for a recommend for promotion and not wishing to get on the wrong side of the gentleman, decided to say nothing and make no defence. Consequently the able seaman and myself were ordered to pay the cost of new fittings, amounting to one pound twelve shillings for each of us. This was pure bluff and we might justly have refused to pay. Had the matter or loss have been logged and reported as storm damage it would have been made good without a question.

In due course the coast guards were landed and loading up with coast guard stores at Devonport, we sailed once again for Bantry, the rendezvous of the parent ship. At Devonport, several of the seamen were relieved by new hands from the depot. All of these men unaccustomed to small craft and the exposure and hard weather that the crews of the cutters had to put up with. Not a man among them possessed an oil coat or a pair of sea boots to keep himself dry. Before we reached Ireland they had their first taste of life on board of a coast guard cruiser.

On the passage in the middle of December the wind north east with a rough sea, the vessel was under a double reef mainsail and labouring heavily. Having kept the first dog watch, just before six o’clock, I was just thinking of being relieved, going below, and taking off the oil clothes for a few hours, when by a most unusual lift of the mainsail the middle peak halyard block at the mast head became unhooked, a very rare thing indeed to happen under any circumstances. The consequence was the sail had to be lowered and the block re-hooked. No easy job of a pitch dark night with the vessel rolling and pitching like a cork. It was useless to order one of the newly joined seamen aloft, he would have no idea what was required and might possibly be flung overboard.

The newly joined mate, a small insignificant officer with no personality, who had served in steam and in a small cutter only, was entirely without hard winter weather experience such as we were having at this time and had little or no idea how to proceed to re-hook the block. I undertook to go aloft giving this officer a hint to see that the block was triced up clear of turns ready for hooking.

Climbing to the masthead, in a few minutes the block was sent up. My first care is that it does not hit me in the head and send me down faster than I came up. It is one hand for myself and one hand to the block; at the same time being violently swayed about that it was only the monkey in our make-up that enabled me to hold on at all. Try as I would the block could not be hooked with one hand. After a while I became exhausted and sea sick and returned to the deck.

Then another man was sent up. Telling him why I had failed and to take a small piece of rope with him and to lash himself to the masthead in order to use both hands. Going aloft and lashing himself in order to free both hands, in two minutes the block was hooked, the sail reset and we are underway once again. That half hour at the masthead on that dark night, being jerked through space with every roll of the ship, was one of my worst experiences.

In due course we arrived at Bantry, remaining a few days, from thence [we] proceeded up the west coast, calling at various stations with stores, not a very pleasant job in the dead of the winter. As to shipping; it was a deserted sea, not a sail or craft of any description in sight. The mountainous Atlantic sea expending its fury on the rocky islets and the ironbound cliffs of the headlands was enough to strike terror into the heart of the bravest seaman.

A few days before Xmas we arrived at Killybegs, a snug little land-locked harbour in the county of Donegal. Orders awaited us to moor up and given fourteen days leave to each watch, with a couple of days over for travelling. As I had not had any leave for just on two years I took this opportunity to get away, if only for a short time, from ship’s life, ship’s food, sea boots and oilskins, and the eternal monotony of the west of Ireland.

In order to reach the railway we had to drive nineteen miles through the wild and mountainous district of Donegal in a jaunting car. Long before daylight four of us set out on this uninviting journey, the rain falling in torrents. Our ardour was not dampened on this account, for we were homeward bound, if only for a brief two weeks. What cared we for a few spots of rain, with the solid ground under our feet? After a four hour drive, we arrived at the town of Donegal and in due time boarded the train for Gourock where we expected to catch the steamer crossing to Holyhead that night.

At four p.m. the train came to a standstill at Strabane. After waiting for a very long time we were informed that we could not go any further that day on account of a block on the line. This was disappointing as it meant the loss of twenty four hours, which we could ill afford out of a bare sixteen days.

The station master directed us to an hotel where the railway company would defray our expenses. A kindly Irish traveller staying in the hotel, in sympathy with us, prompted us to demand something more than our expenses, by the way of compensation for the delay. “Indeed”, he said, “ye should be after getting twenty shillings each of ye”. So back we hastened to the station master and laid our demands before him. He failed to see that we were entitled to any compensation for delay, but after some argument and bargaining he eventually handed us fifteen shillings each.

The day following we proceeded on our journey and arrived at home in time for the Xmas dinner. Needless to say my parents were very pleased to have me with them once again after my long absence.

One of the pleasures of a holiday was the fact that there was no turning out at the call of the watch. Consequently one morning I was rather late in getting down for breakfast when my mother brought me a letter. It was from one of my shipmates with the good news that I was promoted to Chief Petty Officer and was to be transferred to the Squirrel in the Clyde district.

This news was very pleasing to me; I had served seven years and six months on the west coast of Ireland and was only too glad of a change of scene and service. Service on the west of Ireland, scarcely ever touching at any town of importance was nothing more than stagnation, being deprived of all forms of amusement, social life or elevating company.

1888

Early in January 1888, my leave now drawing to a close, I start on my return journey, leaving Mevagissey on a Saturday, travelling in the horse bus to St Austell, from thence boarding a train en route for Holyhead. At Plymouth one of my shipmates joined me and at Exeter another joined our company. Arriving at Chester very late at night the boat train for Holyhead had left, leaving us stranded for twenty four hours. It being so very late and every place closed, we were at a loss to find accommodation. The guard of the train took us to his home, offering us the accommodation of one bed. Three in a bed was rather close quarters, but we did not mind, and treated it as a joke. It was all a part of the holiday fun. As the time came to resume our journey we were not sorry to board the train for Holyhead. Catching the steamer across to Ireland that night and arriving in Donegal town the following morning where a jaunting car was hired for our nineteen miles drive to Killybegs.

After a brief and varied holiday, with the delay on our homeward and return journey, we were truly glad to board our ship where there were cheery shipmates to bid us welcome. I was at once informed of my promotion and that the Squirrel was ordered across from the Clyde to Ireland to make the exchange, a petty officer from the Squirrel taking my place.