The George 1787-1790

23 September 2019Free trader or fair trader?

22 October 2019The Lord Hood of Penzance & St. Ives: Fair Trader or Free Trader? 126 ton Brigantine – 1787-1798.

The Lord Hood was a small merchant vessel of the late eighteenth century. A modest 126 ton brigantine of unspecified origins, she was two masted with a single deck. Described as French built, one significant feature of her construction was not recorded by the Penzance Officers when she was registered there in 1787 – she was clinker built. An unusual construction for a cargo carrying vessel, but one common in vessels built for speed. The Lord Hood may well have been built on one of the islands forming the French West Indies at that period, but unfortunately her original name has not been discovered. She was captured during the American Revolutionary War, being condemned as a prize in the High Court of Admiralty at Barbadoes.

It seems very likely that this vessel may have been the Lord Hood reported in Lloyd’s List of January 14th 1783, as having sailed from St. Lucia in company with the Cunningham on the 12th November 1782. They parted company in lat. 38.04, lon.52.46, on December 10th, and the Cunningham, Capt. Henry, was reported to have arrived at Greenock, from St. Lucia, with sugar, &c., on January 3rd.[*]

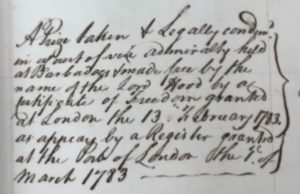

No report has yet been discovered of the Lord Hood’s actual arrival in England, but she was here early in 1783, as she received a Certificate of Freedom in London on February 13th, and when registered at Penzance, in 1787, was described as:

‘A Prize, taken & legally condemned in a Court of Admiralty held at Barbadoes & made free by the name of the Lord Hood by a Certificate of Freedom granted at London the 13, February 1783, as appears by a Registry granted at the Port of London the 1st March, 1783.’ [*]

Pre-dating 1786, this earlier registration must have been in a Plantation Register,[*] but no extant copy of this Plantation Register has been found. Thus the full details of how she came into British ownership, along with her place of build, previous port of ownership and age have been lost with this missing registration documentation. How she came to be owned at Penzance is equally uncertain, but at 126 tons measurement she was a fair sized vessel for that little West of England port, and quite suitable for foreign trade anywhere in the western world, but not built to carry heavy bulk cargoes.

At first she appears to have been commanded by a Captain Qualtro, sailing from the Thames for Gibraltar on March 10th, that year, returning to Gravesend from Malaga on July 31st, having touched at Portsmouth on her homeward passage. She probably brought home a cargo of fruit – fresh or dried. No report has been discovered of her sailing again from the Thames, but she later arrives at Penzance from Ostend.

The first report found of her trading to and from Penzance appears in Lloyd’s Lists for October and November 1783. Under the command of a Captain Hosking[s], she arrived at Penzance from Ostend on 16th of October,[*] clearing out again for Dublin on November 6th.[*] Contemporary reports of her movements are few and far between – which was common enough for vessels predominantly employed in the coastal trades. In the following February, still under Hosking’s command, she again entered Penzance, this time from Oporto,[*] before clearing out for the ‘westward’[*] – probably for Ireland, but just possibly for Newfoundland. Information about her movements over the next two or three years has proved equally sketchy, but in September 1787 she returns to Penzance once more. She must have been in foreign trade, at least since September 1786, as she had not yet acquired ‘British registration’ under the 1786 Act – a condition that was only tolerated if she had not touched at a British port in the meantime.

The first report found of her trading to and from Penzance appears in Lloyd’s Lists for October and November 1783. Under the command of a Captain Hosking[s], she arrived at Penzance from Ostend on 16th of October,[*] clearing out again for Dublin on November 6th.[*] Contemporary reports of her movements are few and far between – which was common enough for vessels predominantly employed in the coastal trades. In the following February, still under Hosking’s command, she again entered Penzance, this time from Oporto,[*] before clearing out for the ‘westward’[*] – probably for Ireland, but just possibly for Newfoundland. Information about her movements over the next two or three years has proved equally sketchy, but in September 1787 she returns to Penzance once more. She must have been in foreign trade, at least since September 1786, as she had not yet acquired ‘British registration’ under the 1786 Act – a condition that was only tolerated if she had not touched at a British port in the meantime.

![]()

As a ‘prize made free’ the Lord Hood – although of foreign build – was accorded all the rights of a British built vessel when she was registered at Penzance on September 27th 1787. Her registered owners were John and James Dunkin, two brothers of Penzance, along with one Thomas Bevan, a London merchant.[*]

As a ‘prize made free’ the Lord Hood – although of foreign build – was accorded all the rights of a British built vessel when she was registered at Penzance on September 27th 1787. Her registered owners were John and James Dunkin, two brothers of Penzance, along with one Thomas Bevan, a London merchant.[*]

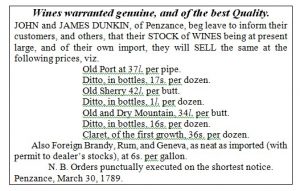

Dunkin advertsiement in the Sherborne Mercury, April 20th, 1789

The Dunkin brothers’ occupation was not stated on this occasion, but they were then well established as wine and spirit merchants.

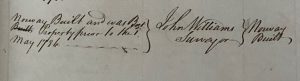

Operating on both sides of the law in this lucrative trade, at the same time the brothers also traded in general merchandise, mining materials and fishery salt, as well as the exportation of salt-cured Cornish pilchards. During this period the Dunkin brothers owned shares in a dozen Penzance vessels ranging from the 25 ton sloop Liberty,[*] to the 202 ton ship George [*] – which they registered at Penzance just two days after the Lord Hood. Although a fair sized vessel by west country trading standards, the Lord Hood was only 69 feet long, with a beam of 22 feet, and an internal depth of 10 feet 2 inches in the hold, and as a clinker built vessel she was probably fine-lined, and not very burthensome, but she was slippery. Now commanded by one William Michell [sometimes spelt Mitchell], she (along with the George), appear to have loaded hogsheads of salt-cured Cornish pilchards for the Mediterranean that autumn. British trade with the Mediterranean then required a special pass, supposed, as part of a treaty with the Bey of Algiers, to prevent seizure and detention by Algerine pirates. In this period, as a regular trader, she was manned by a crew of seven, including her master.[*]

The issue of these passes was controlled by the Admiralty Office, in London, but they had to be obtained through the local Custom House – which also controlled the registration of shipping and the issue of all essential permits, cockets and sufferances required for a British vessel top trade overseas. The Penzance Customs officers duly passed on Messrs. Dunkin & Co’s application to the Secretary of the Admiralty in respect of both these vessels. –

Philip Stephens Esq.r

Sir, Please to order a pass to be sent me for the George of this port John Ward Master, Norway Built British Property, also a pass for the Lord Hood (French Built made free) William Mitchell M.r agreeable to the said Certificate & Masters’ affidavit Inclosed.

I am Sir &c. E G [Elias Govett]

CustomH.o Penzance, 26th Octo.r 1787 [*]

Elias Govett was then Acting Collector of Customs at Penzance – the established Collector, John Scobell having been suspended pending enquiries – though he was later re-instated. It seems that Captain Michell’s original request was made through Scobell on October 12th, that being the date noted against a remittance of £1 5s. 0d., when the accounts were eventually returned to King’s Beam House in August 1788.

Fully loaded the Lord Hood sailed for Naples during the week ended November 22nd,[*] but the George was detained at Penzance due to bureaucratic semantics. As a foreign built, British registered vessel, she had tried to import a cargo from North America – a trade which was restricted to British and Plantation built vessels. [*]

The voyage out to Naples would have taken about four or five weeks, but these were uncertain times, and reports from the Mediterranean took a similar length of time to reach Britain. Accordingly, contact between ships and owners in England was broken for several months or more. Eventually her undated arrival at Naples, along with that of another pilchard trader – the Penzance, Captain Quick [*] – was reported in Lloyd’s List of Friday February 1st 1788. Both vessels were reported as having arrived there from Falmouth, rather than Penzance, but this was quite normal for these times. Mediterranean convoys then assembled at Falmouth prior to sailing.

At the end of March the Lord Hood was reported as having arrived at Barcelona from Saloe,[*] and on May 17th she was again off Penzance – allegedly to perform quarantine. Although not a recognised quarantine station as such, Penzance like most Custom House ports had amongst its staff designated quarantine officers – albeit that they usually doubled up with other Tide Waiter’s and Boatman’s duties.

Irrespective of whether there had been any disease on board, vessels coming in from foreign voyages were required to fly the ‘yellow flag’ until they obtained ‘practique’ or clearance from the local Superintendent of Quarantine. A process which required the captain to answer a set of questions, and make a statement on oath [sworn over a ‘quarantine bible’ suspended on a suitable long pole], that there had been no unexplained deaths or illness during the passage, or otherwise. And, further depending on where the vessel had come from, and the answers given to the set questions, a vessel was either given clearance or placed under restraint of quarantine. The actual period of detention under quarantine served varied with circumstances. However, a practice had developed of vessels calling at Penzance to make their quarantine declarations, before continuing on their voyages to their port of discharge. This started the clock on any potential quarantine period and vessels could proceed before this period had expired on the assumption that the clock would run down by the time they reached their final destination. Thus effectively minimising and potential delay and detention. Unfortunately this practice was frequently abused, and ‘distress of weather’ was often used as an excuse to enter port before practique had been granted. In addition the practice was used as an alibi for being off course.

Such then seems to have been the Lord Hood’s master’s intent when her arrival in Gwavas Lake, off Penzance on May 17th 1788, aroused the suspicions of the Customs and Naval officers.

Captain John Salisbury, RN, recently appointed to the command of HM Sloop Termagant, assigned to patrol the western waters of the English Channel, had been particularly warned to be on the look-out for smugglers. After a week patrolling between Start Point and the Lizard, during the afternoon of the 17th he weathered the Lizard and put into Mount’s Bay. Tacking up into light northerly breezes all night, at 7:30 the following morning he ‘brought too ye. Lord Hood Brigg of Penzance, from Sette bound to Dunkirk, sent a Boat with an Officer on board her.’ Captain Salisbury was justifiably suspicious. The wind was fair for Dunkirk, but foul for Penzance. At half-past nine he sent an officer ‘to the Custom House at Penzance to procure Intelligence of the above Brigg.’ When Termagant’s cutter returned just after noon, the answers he received must have confirmed his suspicions, as he appears to have resolved to keep a special watch on this vessel.[*]

Meanwhile the Lord Hood continued to beat up into the bay, and at half-past three Capt. Michell anchored his vessel ‘abreast of Penzance.’ An hour later the Termagant also came to an anchor in 8 fathoms of water in Gwavas Lake – or ‘Guavas Lake’ as recorded in Captain Salisbury’s log. However, unlike four other vessels arriving about this time:[*]

| Polly | Thomas Wharton | Malaga, last from Gibraltar | for London | 9th May |

| Betsy | William Uren | Gallipoli | for Bruges | 19th May |

| Commerce | Mitchell | Gallipoli | for Hamburgh | 20th May |

| Penzance | John Quick | Gallipoli | for Rotterdam | 20th May |

William Michell, the master of the Lord Hood, chose not to make a quarantine declaration on this occasion, though he may have done so a few days earlier when at Scilly – as Capt. Salisbury was later to report. Certainly nothing was made of this at Penzance, and there are no other entries relating to her in the Penzance Custom House letter-books at this time. Neither was there any reference to Captain Salisbury having sent a Lieutenant ashore to enquire of them about the little brigantine.

The weather in Mount’s Bay continued fine with light airs, and at 21:00 on the evening of the 18th, under cover of darkness, Captain Salisbury sent off two armed parties, one in the cutter and the other in the pinnace, ‘to look for smugglers, and intercept any Boats that might pass from the Brigg to the Shore.’ It proved a fruitless night, and the boats returned at 4 am without encountering any illicit traffic. The following night an armed boat was sent out to keep guard around the brig, but at half-past midnight the Lord Hood hove her anchor and resumed her declared voyage to Dunkirk. Meanwhile, just before midnight the pinnace had been sent off with an officer to examine another suspicious boat, which proved to be a legitimate trawl smack. This all took time and it was half-past four before Termagant’s pinnace returned and she could resume shadowing her quarry down the bay towards the Lizard. Those three or four hours might have been crucial, and certainly allowed sufficient time for the Lord Hood to send a boat ashore at Prussia’s Cove, and appraise the brotherhood of his immediate intentions.

Noon of the 19th saw the Termagant some two miles to the south’ard of the Manacles, with the brig about 5 or 6 miles ahead bearing ESE. Throughout the first part of that day her crew had been kept busy firing guns and putting off in boats to bring to several small craft, all of which proved to be legitimate fishing vessels. In the latter part of the forenoon, the weather was so calm that neither vessel was making much headway, and every zealous Captain Salisbury and his Master, put off in the cutter to take soundings around the Outer Manacle Rock.

About three pm they resumed their leisurely pursuit. With a light northerly breeze off the land both vessels continued to run quietly up Channel until just before midnight. With the Lord Hood then four or five miles ahead, the wind swung into the east heading them. Termagant was now near the easterly extent of her patrol area, and after speaking the British Queen from Alicante for London, Captain Salisbury gave up this apparently fruitless chase, wore ship and headed back down Channel to the westward.

A little over 24 hours later the Termagant anchored off Falmouth in Carrick Road, and the following day Captain Salisbury wrote a long letter to the Board of Customs, about his suspicions, and his recent actions.

Termagant, in Carreg Road Falmouth, 22nd May 1788

Gentlemen, Being appointed by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, to prevent and correct all illicit Practices, carried on by the Smugglers upon this Coast (from the Dodman to the Land’s End) I must beg leave to acquaint you of an abuse, made use of frequently in Mount Bay; The Vessels that go from thence for the Ports in the Mediterranean, laden with Fish generally return with a Cargo of Brandy, said bound to Dunkirk, or some french Port, instead of prosecuting their Voyage, (under a pretence of wanting some trifle) they Anchor in Penzance Road, with a fair Wind, merely to wait an Occasion for Smuggling their Cargo, their not having performed Quarantine, prevents Search, or Custom House Officers on board; The Communication with the Owners, and Other People on shore is likewise very dangerous; I have just had a recent, and glaring Example of a Brigg, (whose Master, and Owners, are both known to be Smugglers) returning from Sette, With a Cargo of Brandy bound for Dunkirk, I met her within the limits; She had been some days at Scilly, where she certainly might have been furnished with every thing necessary for the remainder of her Voyage, notwithstanding which she Anchored again at Penzance, and remained thirty six hours, The Deputy Collector of the Customs, to whom I sent a Lieutenant on the Subject was convinced of the impropriety, and I dare say used every Vigilance to send her to Sea. I followed her to the Eastward of the Start, and left her, Steering the Channel Course.

I think it a Duty incumbent on me to make those remarks, to you Gentlemen, and I dare say the Collector of the Customs at Penzance will receive from the Board, some instructions to prevent in future Vessels coming there, under Quarantine from frivolous excuses, merely for the purpose of Smuggling.

I have the Honor to be, Gentlemen, Your most Obedient Servant, (Signed) Jn:o Salisbury

(A Copy) To The Commissioners of His Majesty’s Customs, London [*]

Intriguingly Salisbury does not name the Lord Hood. For propriety, and of course to ensure that the Admiralty Board appreciated that he was actively following their Lordships’ orders, a copy of this letter was submitted to the Admiralty Office, along with a covering note to Phillip Stephens, the Admiralty Secretary.

Termagant, in Carreg Road Falmouth, 22nd May 1788

Sir, Please to acquaint my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, of my arrival here, who will perceive from a Copy of a Letter, wrote to the Commissioners of the Customs (which I have the honor to enclose for their Lordships) what service the Sloop under my Command, has been Employed upon.

Jn:o Salisbury

Philip Stephens Esq.r [*]

About this time the Penzance Custom House establishment was going through a troubled patch. As noted above the established Collector of Customs Mr. John Scobell had been suspended from duty for over twelve months, due to some alleged impropriety or other. Eight other members of staff – Tidewaiters, Boatmen, or Coal Meters were summarily dismissed for undisclosed irregularities on May 25th. By inference Scobell was initially tarred with the same brush, but in time managed to convince the Commissioners of his innocence. Accordingly, on the 8th of August John Scobell was re-admitted and sworn once more into the office of Collector of Customs at Penzance, after finding two bondsmen, Thomas John and John Ellis, two Penzance merchants to provide security in £2,000 for his faithful execution of his duties – the latter of whom was an active partner with the Dunkins. The administration of the Penzance office now regained a semblance of normality. In the interim, no doubt, a number of omissions and minor irregularities must have passed un-checked, and it was probably this hiatus that enabled the foregoing Lord Hood incident to pass unrecorded by the acting Penzance officers.

Three months later, there was a belated exchange of letters, sparked by one from the Board of Customs.

N.o 80. Custom House London, 23.d August 1788.

Gent, The Commissioners having received Information that a Brigantine called the Lord Hood William Mitchell Master belonging to Penzance took on board at Jersey the 8th Inst thirty pipes of Brandy, ten of Geneva, and three of Wine, and cleared out with the same for Corona in Spain, but it being Supposed that the said Brandy &c will be attempted to be landed in some part of Cornwall;

I have it in command to direct you to communicate the said information to all the Officers of your Port, particularly to those of the Water Guard, as likewise to the Commanders of such Admiralty Cruizers as may be Stationed at or in the Neighbourhood thereof, and to excite them in the Strongest Manner to keep a good lookout, and to use their utmost endeavours to intercept and prevent any Frauds that may be attempted to be committed by the said Vessels, taking Care to apprize the Board of any matter thay may arise in consequence thereof fit for their cognizance.

I am &c. John Gale [*]

To which the Penzance Officer replied:

No. 67, Custom House, Penzance, 29th Aug.st 1788

Honble Sirs, In obedience to your Hon.rs orders Signified to Us by Mr. Gale in his Letter of the 23rd Inst. N.o.80. We immediately communicated its contents to the Officers of this Port, particularly to those of the Water Guard. & likewise to Captain Salisbury of His Majesty’s Ship Termagent; & Capt.n Richard John of the Dolphin Cutter in the Service of this Revenue, We humbly beg leave to represent to your Honble Board, that the Brig Lord Hood sailed from this port on the 3rd Inst. when the Captain declared to the Tidesurveyor that he could not say exactly where he was bound, but he believed he should go to Crozic for a Cargo of Salt, and on the 13th following he again arrived in this port. The Captain being gone on shore when the Tide Surveyor boarded her he enquired of the Mate from whence they came, who told him that they came from Torbay, & that they had met with a Dutch East India Man, had taken the Passengers off her and landed them to the Eastward (the Surveyor rummaged her but could not find any prohibited or other Goods on board) this we conceive must be a wrong report, as it appears from the Information received that she was at Jersey the 8th following & we are of Opinion that she could not have gone from Jersey to Carona in Spain, landed her Cargo and returned again to this Port in the Short space of five days which she must have done. – We have the greatest reason to believe that this Vessel has been for some time in an illicit Trade on the Coast of Wales and Cornwall. She is now daily expected to Arrive from Crozic with a Cargo of Salt, we have therefore excited all the Officers belonging to this port in the Strongest manner to exert themselves and to use their utmost Endeavours to detect her, should the Captain attempt any Frauds; – should there any new matter arise fit for the Cognizance of your Honble Board we shall take care immediately to acquaint your Hon.rs therewith.

We are &c. S. and W.

P.S. Capt.n John is now here and has likewise engaged to keep a good lookout for her. [*]

This presents a confused picture of her alleged movements and in this Scobell conceived that there must be some element of mistaken identity. As fast a vessel as she undoubtedly was, the Lord Hood could not have called at all the places claimed in the time available. Even so Scobell is vague, perhaps deliberately so, about which elements of the voyage and/or ports of call he thought were suspect.

HM Sloop Termagant was off Penzance again on August 27th and 28th, and no doubt John Salisbury welcomed the chance to pursue his old quarry once more, but apparently with no greater success than before.

The officials at London duly wrote back emphasising the lack of material evidence, and exhorting the Penzance officers to greater efforts.

No. 99, Custom House London, 7.th Septem.r 1788

Gentlemen, The Commifsioners having read your Letter of the 29.th August N.o 67. relative to the Brigantine Lord Hood, William Mitchell Master belonging to your Port supposed to be employed on an illicit Trade.

I have their directions to acquaint you that the same affords but Slight Evidence thereof, and they direct you to report whether any further Evidence can be procured, and if any of the persons belonging to the Vefsel can be prevailed upon (not by improper means) to give information respecting her.

I am &c. William Watson, in the Secret.y absence [*]

The closing sentence of this letter and the importance of obtaining evidence by proper means will have significance later. Despite the best efforts of the local officers at this time no more-incriminating information was forthcoming, and the Lord Hood, her master and crew, remained at large.

One month later she again loaded a legitimate cargo of salt-cured pilchards at Penzance for Naples, clearing out for the Mediterranean about the 7th of October. As on her previous Mediterranean voyage, the news of her safe arrival took some time to reach England, and being published in Lloyd’s List of December 26th. Following a similar pattern to the previous year nothing more was heard of her until her arrival off Penzance early in April 1789. Now on a declared voyage from Barcelona to Havre de Grace, just why Michell found it necessary to put into Penzance during such a voyage does not seem to have been challenged or explained. However, she did on this occasion follow normal procedures for clearing quarantine.

Custom House Penzance, 6.th April 1789, No. 62.

Honble Sirs, Inclosed we beg leave to transmit y.r Honble Board the Quarantine Questions and Answers of Captain Mitchell M.r of the Lord Hood bound from Barcelona to Havre de Grace laden with Brandy and Wine, the Crew have been mustered and appear to be all in good Health, and we have ordered the Vefsel under Quarantine.

We are &c. [J.G] [J.W] [*]

No copy of Mitchell’s answers to the questions was kept, and the summary entry for the Lord Hood being endorsed ‘no order of Disch:’ indicates that she too sailed from Penzance before completing her full term of Quarantine. A course of action that applied to eight of the ten vessels so listed that year.

Before resuming her voyage, the Lord Hood spent six days at anchor in Gwavas Lake under quarantine, and ostensibly under the close attention of an armed guard constantly rowing around her – extra men being employed in this duty. The detailed accounts presented in the Port of Penzance’s annual return to the Board of Customs of ‘Extra Service performed by the Officers of this port on Quarantine from 5 January 1789, to 5 January 1790.’, list ten vessels as performing quarantine there during that period. Six of these were Penzance registered vessels, but none of them were bound for Penzance. Indeed, only one of them was destined to discharge at a British port!

Along with details of the service to the other vessels under quarantine this return records that.

Thomas Waron Surveyor and Superintend.t of Quarantine, attending on the Lord Hood William Michell M.r from Barcelona 6 days at 2/6 p-day. — 15s.

Thomas Doble, Thomas Rowe, Mich.l Donnithorne, John Perryman, & Charles Lander – 6 days each, & William Cary 2 days all Boatmen attending on the above Vefsel 32 days at 1/ — £1 12s. [*]

What Captain Michell and his crew actually did during those six days of supposed isolation is open to speculation. There are suggestions that some form of communication with the shore took place – either by shouting, writing, or physical contact – when arrangements were possibly made for a later rendezvous.

Whatever, on April 12th, after six days at anchor off Penzance and still supposedly under quarantine, the Lord Hood sailed for Havre de Grace. Probably putting to sea in the early hours of the evening, what could be simpler than to heave to off Prussia’s Cove a few hours later. Run at least part of the brandy and wine ashore under the cover of darkness, and stand off well before daylight, clearing the Lizard later that morning with no one in authority being any the wiser.

About the 23rd of May, shortly after another Prussia’s Cove incident concerning the Penzance sloop Success, the Lord Hood called in off Penzance from Havre de Grace, before continuing on another undisclosed voyage. Six weeks later she was back at Penzance, now from Croisic, presumably with a cargo of French salt for the fishery.[*]

On the night of the 29th of August 1789, the Lord Hood was hovering on the coast of Cornwall when she was discovered by Capt. John of the St. Ives Revenue Cutter Dolphin, in the act of running contraband goods ashore at Prussia’s Cove. Caught in the act, securing the seizure and taking up some of the cargo took Capt. John until daylight. Then, his seizure secured, instead of carrying his prize into the nearest harbour – Penzance – Capt. John took her round the land to St. Ives. While Mount’s Bay lay within Dolphin’s normal patrol area, she was actually part of the St. Ives Custom House compliment. Like many revenue cruisers of her era she was not owned by the Commissioners of Customs, but was a private vessel hired by them from John Knill – who as the Collector of Customs at St. Ives, had a personal financial interest in any prizes seized – a factor which must have had some bearing on Capt. John’s decision to carry her round to St. Ives. It was a highly irregular action, and was certainly not because of the prevailing weather, or any other practical consideration. The Penzance Officers, having lost a share in any related seizure reward, complained bitterly to the Commissioners.

Gentlemen, I beg leave to represent that on Saturday Night of the 29th Ultimo, the Dolphin Revenue Cutter commanded by Mr. Richard John fell in with, and detected the Brig Lord Hood of this port, running her Cargo consisting of about Forty Pipes of Brandy & Geneva at Prussias Cove (otherwise Porth Knowles) within this Bay, which was Seized by the said Mr. Johns and Crew; from part of the Goods being alongside rafted, a considerable time was taken up in Hoisting it on board again, which detained them untill morning, when to my utter astonishment instead of bringing the Seizure to this Warehouse, which could have been done in the Space of an half hour, the said Cutter, and Brig made Sail with the wind direct a Head for the port of St. Ives, which employed all that day, and night and part of Sunday to effect: as I am at a loss to account for proceedings so very unjustifiable, and contrary to the Honble Boards orders in this case which affords so great an opening for Embezzlement, if Commanders of Revenue Cutters are permitted from Caprice or partiality to carry their Seizures to any Custom House they please, request you will lay this transaction before their Honors, that Captain Richard John’s disobedience of Orders may meet with an impartial Investigation.

I am Gent. Jos. Webb, D-Com

Custom Ho. Penzance, 5th Sep.r 1789 [*]

However irregular Captain John’s course of action might have been, there seems to have been no effective redress for the Penzance officers, and the vessel and her contraband cargo were duly prosecuted and condemned through the St. Ives office. For security, once the formalities had been completed, the Lord Hood was brought back to Mount’s Bay again, and moored in the Mount harbour pending receipt of disposal instructions from the Board of Customs. Here she lay under Capt. John’s watchful eye until her sale was eventually advertised to take place at St. Michael’s Mount.

The reasoning behind this shift must be due to the lack of suitable moorings in St. Ives harbour, which was prone to heavy run under certain weather conditions, and potentially hazardous for fine hulled craft. Only days after the Lord Hood’s seizure, the New Exeter Journal [a provincial newspaper that carried elements of smuggling news] of September 10th 1789, reported that she had arrived at Penzance from St. Ives ‘since my last’ – a standard phrase used by regular correspondents. St. Michael’s Mount lay within the limits of the Port of Penzance (which extended from The Lizard to Cape Cornwall) and which explains this apparent confusion in names. The transfer of this prize back to their patch can only have served to further annoy the Penzance officers with Captain John’s cavalier behaviour.

However, the Mount was normally a very secure harbour, and St. Michael’s Mount was also Captain Richard John’s home, his shore-side place of residence. Accordingly the Dolphin was regularly berthed there. Beyond a nominally more secure berth, and the factor of allowing Captain John to keep a close eye on his seizure there appears little material advantage in making this shift. But it is conceivable that Collector Knill and Captain John thought they would more readily find a buyer nearer to the Lord Hood’s home port!

![]() After due process the Lord Hood was condemned in the Court of Exchequer as a legitimate seizure on the 18th November 1789, and her Penzance registration was endorsed.[*]

After due process the Lord Hood was condemned in the Court of Exchequer as a legitimate seizure on the 18th November 1789, and her Penzance registration was endorsed.[*]

But this endorsement was undated. Under standing orders her hull should then have been cut into pieces to prevent her ever again being employed as a smuggler – or indeed as any kind of vessel.

Cutting up a condemned smuggler

Condemned Vessels

1795 13 Aug.t The following Rules to be observed in breaking up Condemned Vessels: Ballast, Masts, Pumps, Bulk heads, Platforms and Cabins to be taken out. The Decks, if any, ripped up fore and aft, and the Beams sawn asunder in two places, viz.t one on each Side of the Main, and other Hatchways, from end of the Vessel to the other. The whole of the top sides Wales Planks on the Bottom to be ripped off, the Keel cut into four, and the Stem and Stern posts into three pieces each.

Open Boats to be cut through their Thwarts in two pieces each, the Hull sawn into four equal parts athwart Ships, and fore and aft from Stem to Stern, and the Stem and Stern cut into two pieces. [*]

However, as a valuable prize the Lord Hood was ordered to be sold on the open market rather than cut up and dismantled. The proceeds of the sale were to be divided between the Crown and the seizing officers, and the impending sale was widely advertised in the London and provincial newspapers, as well as by bill posters.

PORT OF ST. IVES

By order of the Honourable Commissioners of his Majesty’s Customs,

on Tuesday the 16th day of February instant, by two o’Clock in the Afternoon, A Public Survey will be held at the House of James Matthews, innkeeper, on St. Michael’s Mount, for the Selling whole,

THE BRIGANTINE LORD HOOD,

Burden 124 24-94th Tons, by admeasurement, together with all her Materials; and the day following (being Wednesday) by two o’Clock in the Afternoon, will be exposed to Public Sale, at St. Ives, aforesaid, the Hulls of a Sloop burden 15 Tons and a Boat 10 Tons, whole, together also, with their several Materials, and likewise the broken up Hulls of two other Boats.For further particulars respecting the said Brigantine Lord Hood, application may be made to the Collector and Comptroller of the Customs at St. Ives, or to Richard John, Commander of his Majesty’s Revenue Cruiser, Dolphin, at St. Michael’s Mount, aforesaid, who will shew the same to any person or persons inclined to purchase.

Times, (Fr) 12th February, 1790.

Whatever Knill and John may have thought about attracting a ready buyer at the Mount it did not prove an effective gambit. While Penzance was technically her Port of Register, the Dunkin brothers held very strong trading connections with the Mount, and did most of their legitimate business there. Perhaps the word was put out; perhaps a reserve price was not reached – we shall never know – but there was no buyer in February 1790, and two months later the vessel was re-advertised.

PORT OF ST. IVES, Cornwall.

By order of the Honourable Commissioners of his Majesty’s Customs,

on Tuesday the 20th Day of this instant April, by Three o’Clock in the Afternoon, A Public Survey will be held at this Office, for the sale and disposal of,

The LORD HOOD, Brigantine,

to be sold whole, together with all her Materials, now lying at St. Michael’s Mount, and there to be delivered.

For Particulars Application may be made to the Collector and Comptroller, at St. Ives aforesaid, or to CAPTAIN RICHARD JOHN, at St. Michael’s Mount, aforesaid, who shall shew the said Brigantine to any Person inclined to purchase.

Custom-House, April 9, 1790.Exeter Flying Post, (Th) 15th April, 1790.

While the St. Ives officers continued to try and find a buyer for their prize, the Penzance officers were left with the administrative task of sorting out the uncancelled bonds made for the ‘good behaviour’ of the Lord Hood’s master and mate.

Custom H.o. Penzance, 5th March 1790

Honble Sirs, We humbly beg leave to Acquaint your Honble Board that there is now in our Custody a Master and Mates Bond given in the Year 1787, by Captain William Mitchell & Richard Brown Mate of the Brigantine Lord Hood, belonging to this port, which Vessel was some time since Seized by Captain Richard John of the Dolphin, for attempting to Smuggle on Shore a Quantity of Brandy and Geneva, and Carried into the Port of St. Ives.

We are &c. [J.S.] [J.W.] [*]

At one time I had hoped to find the ‘office copies’ of these bonds, but when the staff at the Public Record Office [National Archives] advised me that they lay off-site and unsorted in several trunks, I balked at the prospect. These bonds were then an every-day feature of British maritime trade at home and abroad, being a promise to pay a penalty in the event of breaches of behaviour of masters and mates on voyages. They should now have been declared forfeit and the sum assured by the bondsmen demanded. One would have also thought that there would have been some statutory punishment meted out to Michell and Brown – but perhaps they were not taken when the Lord Hood had been seized. Whatever, we have no record of this, and it does not seem to have materially affected either of these mariners. They continued in the merchant service, and Michell appears to have later regained command of the Lord Hood.

Once again the St. Ives Customs officers found no buyers for the Lord Hood at the April sale, and unfortunately there are no surviving Custom House letter-books for St. Ives to throw any more light on this part of the story. Perhaps they were frustrated by a concerted attempt to get her restored by her previous owners – a suggestion which is partly born out by later remarks made by Helston attorney Christopher Wallis in his journal for 1793. Whatever the cause of this delay, it was over a year later before she was again advertised – a delay which could have done little to improve her value. This time she was offered as part of a general Custom House sale, along with another vessel and other seized goods.

PORT of ST. IVES.

By order of the Honourable Commissioners of his Majesty’s Customs,

ON Monday the 8th Day of August next, by Two o’Clock in the Afternoon, a public Survey will be held in this Office, for the Disposal of the Goods undermentioned:

For private Families.

BRANDY – 783 Gallons

RUM – 297 Gallons

GENEVA – 2567 Gallons

COFFEE – 180 Pounds

CHOCOLATE – 3 Pounds

BLACK TEA – 13 Pounds

One Bag damaged FLOUR

BUILDING BRICK – 3350

TO BE SOLD WHOLE,

The BRIGANTINE LORD HOOD, burthen per Admeasurement 124 & 24/94ths Tons.

Sloop SUCCESS, burthen 41 Tons per Admeasurement; and three OPEN BOATS, with their several Materials.

The Goods will be set up in several Lots, and sold to the highest Bidder, and may be viewed and tasted three Days before (Sunday excepted) and on the Day of Sale.

Custom-House, dated the 28th July, 1791.Exeter Flying Post, 4th August, 1791.

Even after this final advert, there is some confusion as to whether or not she was actually sold, and if so to whom – but no further sale adverts have as yet been discovered.

In error, both the Penzance and St. Ives Tide Surveyors claimed her as being currently registered at their respective ports in their annual returns of September 1792. No doubt due to an oversight on the part of the St. Ives officers, and while her Penzance registration was eventually cancelled on her re-registration at St. Ives, this entry was not dated.[*]

Although condemned for smuggling in Michaelmas Term, 1789, she was not re-registered at St. Ives until the 10th of April, 1792.[*] The Lord Hood was then re-measured by William North, the St. Ives Tide Surveyor, when he found her to be 71 feet in length – two feet longer than previously recorded. This extra length, when figured into the tonnage formula, gave her a new registered tonnage of 133 tons. North also records her as ‘clinker built’ – a very distinctive feature. This build was quite unusual for a vessel of her size and employment. Clinker built hulls were not renowned for carrying bulky cargoes – especially for vessels constantly taking the ground in tidal ports, creeks and coves. The type of build was of material significance in identifying specific vessels, and one can only speculate why the Penzance officers had not previously recorded this fact. Such key points of identification were crucial to the effective operation of the 1786 ship registration act, and a scan of the Fowey registers will show that this feature was constantly remarked on by them in picking out potential smuggling vessels – though the officers there still registered them!

For some reason John Dunkin was permitted to re-register her as his property. It is not certain why this was permitted. Normally anyone associated with smuggling was proscribed from owning any further shares in merchant shipping. Lacking the written evidence, one can only assume that having been originally condemned, she was now restored to her original owner by some legal process.

The foregoing machinations were all the more remarkable on account of concurrent developments concerning John Dunkin’s brother James – another of the Lord Hood’s previous owners. James Dunkin had recently become a wanted felon – an outlaw – following the murder of two Customs Officers. William Millet and John Oliver were shot dead during the attempted seizure of the Dunkins’ sloop Friendship off Tresco on the night of August 25th 1791. Gunfire had been exchanged and James Dunkin, who was actually on board at the time, was cited as the principal antagonist in the ensuing reward notice of September 8th that year. In this £500 was offered for information leading to Dunkin’s conviction, or that of any of the smugglers involved. James Dunkin did not surrender for trial. He was never taken and appears to have been outlawed as a result. Just where he went remains a mystery to this day, but he disappears completely from public view.

Shortly after this murderous exchange the Dolphin intercepted the sloop Liberty (a sister ship to the above mentioned Friendship) just as she approached Prussia’s Cove on a presumed smuggling run. –

Collector and Comptroller Penzance

Gentlemen, I beg leave for the Honorable Boards information to acquaint you that yesterday about 6 Oclock in Morning off the Lizard I fell in with a Sloop who informed me she came from Roscoe [Roscoff] in France, bound to North Bergen. On first discovery she was steering in Northward for the Lizard Land, wind EbS. but after being [hailed ?] by the Dolphin she bore away and steered North West for the Lands end, but when aBout the Middle of Mountsbay she again altered her Course, by hauling the Wind to the N.E. towards a Noted Smuggling Cove where a Battery of Nine large Cannon are mounted and well known to you by the name of Trenowls, alias King of Prussias or Carter’s Cove, when within two miles of that place I cutt her off by Sailing twixt her and the shore, she then bore away and Voluntarily anchored in the Mount Road, as did the Dolphin – On boarding & examining, I found her to be the Liberty of this place, having on board twelve pieces Containing about 130 gallons each of Geneva on her Ballast, and is the identical Vessel represented to be aiding the Friendship Brig, about one month since at the Islands of Scilly when the Officers were Murdered – I found by her Register she belonged to John & James Dunkin of Penzance, and the last Master Endorsed thereon was at your Office the 30th May 1789, to John Love as Master, who you must know have long since quitted her and is now Master of another Vessel belonging to your Port. Since him others have Commanded her, and at present John Tremethack claims that title, neither of which appears on the Register – In consequence hereof I think it my Duty to detain this Vessel hereby delivering her into your Charge for the Honorable Boards directions, which I trust will speedily be transmitted as I am threatened by John Dunkin with a prosecution for delivering the Register into your hands and humbly hope the Honble Board will also give directions about her Cargo, as it will detain the Dolphin in Port for the better Security of the whole.

I am &c. Richard John.

Dolphin Cutter, Penzance 26th Sept.r 1791. [*]

Even though ‘Roscoff for North Bergen’ was a know euphemism for a smuggling voyage, the twelve pieces, or pipes, of Geneva – being casks of a legal size – were not in themselves contraband. Despite Captain John’s justified suspicions, her papers clearing her from Roscoff for North Bergen were all in order and could not be challenged. In the event he could only hold her on the technicality, that a change of master had not been legally endorsed on her Certificate of Registry. That this change of master had taken place in the French port of Roscoff and that such an endorsement could only be made by British Custom House officers until she returned to a British port, was ignored. The fact of this irregularity only came to light in a subsequent petition for the Liberty’s restoration two years later.

The crew of the Liberty when detained included one Richard Ford, who was suspected of having been one of the crew of the Friendship when the Customs officers were killed. No proof of this suspicion was forthcoming, but Richard Ford appears again later as one of the crew of the Lord Hood, at a material time.

For a brief period the mention of the Prussia’s Cove battery in Captain John’s report seems to have sparked the interest of the Customs Commissioners, and in time honoured fashion they asked the Penzance officers to submit a further report, which was duly complied with. –

Custom Ho. Penzance, 6th October 1791

Honble Sirs, In obedience to your Honors Commands Signified to us in Mr. Hume’s Letter of the 28th Ulto. No.40, We beg leave to acquaint your Honble Board, that we have [made] a particular enquiry respecting the Battery at Prussias Cove within the Limits of this Port, and find that there is one Errected mounting Nine, 6 pounders, and which the smugglers have frequently made use of by firing on the revenue Cruizers and their Boats and driving them off the Coast, particularly on the 9th November 1789, by their firing on the boat belonging to the Dolphin, as was represented to your Honors with our Letter of the 11th Novem.r 1789, No.134. Which enclosed one from Capt.n John setting forth that transaction.

We are &c. J.S, JM [*]

But nothing more appears to have come of it on this occasion. The legal status of a small private shore battery in these turbulent times was not the immediate concern of the Commissioners of Customs.

The Lord Hood having been restored to John Dunkin, she was now legally permitted to sail and trade once more. Old habits died hard, and Dunkin was in no way cowed or deterred by recent events – after all free trade was free trade. It was big business and it was his business. Just what Cap’n Michell and the Lord Hood were up to at this time came out in evidence to the Court of Exchequer over a decade later. In 1801 Guernsey ‘merchants’ Carteret Priaulx and Co., were in dispute with John Dunkin over smuggling debts. Submitting a Bill of Complaint, Dunkin sought to obtain the return of a £300 bond, claiming that the original loan it covered had been cleared years ago. Counter-challenged by Carteret Priaulx and his brothers, both parties submitted accounts to justify their claims. For the cause in hand the fact that these were accounts of smuggling transactions seems immaterial – but smuggling accounts they clearly were.[*] The accounts submitted by Priaulx and Co., recorded that William Michell had commanded the Friendship on three smuggling voyages between May and August 1791, carrying brandy and gin on account of John Dunkin, to the value of over £700. Following her restoration to John Dunkin, Michell resumed command of the Lord Hood, and in January 1792 Dunkin was invoiced for unspecified goods to the value of £1,888 9s 2d, by that vessel. This cause rambled on for years, and while the final outcome was in Carteret Priaulx’s favour, the details of the final judgement are yet to be discovered by me. [*]

On or about the 12th of June 1792, events again came to a head when there was a concerted raid on Prussia’s Cove. This involving the notorious Carter Brothers and their coastal battery of six-pounders; Captain Michell and the Lord Hood; Captain John and the Revenue Cutter Dolphin; the Penzance Customs Officers and Volunteer Militia; Excise Officers and troops from Truro, and the Excise Cutter Fox, Capt. Kinsman, of Falmouth. In many respects it was a partial re-run of the 1789 incident at Prussia’s Cove, with different versions of events coming to light from different official sources.

One version of events came to light through Penzance Custom House correspondence in December 1792, when one John Thompson (a late mariner on board the Revenue Cutter Dolphin) petitioned the Board of Customs for a personal share in the seizure money. But slightly different accounts were later presented at Charles Carter’s trial in February 1793.

Thompson’s petition to the Commissioners of Customs claimed:

To the Right Honorable the Commifsioners of his Majesty’s Customs, London.

The Humble Petition of John Thompson late Mariner on Board his Majesty’s Cutter the Dolphin Employ’d in the said Customs

ShewethThat your petitioner did at the great Hazzard of his Life on the twelfth of June last whent down To Carters Terclores known by the Name of Prufsia Cove where he made a discovery of some Spirits which had been landed with an Intention to defraud the King of his Dutys, which by giving a due Information to Justice Giddy Esq:r a warrant was granted on my information. As it could not been done by any other means then by my discovery, which being made A party of Soldiers was sent for, who whent down with the Officers of the Port to the aforesaid Cove, where we found Eight Six pounders Loaded and Pointed to the Different roads to hinder our approach. But on seeing the Soldiers they made off. Then we proceeded to the Cellars were we suspected the Goods was Concealed, where we found George Blewett who demanded to know what we wanted, when the warrant being produced and the keys demanded he denied having of them and dared us to proceed any further. On that I took up a large piece of wood and attempted to break open the Door, but that being so well secured I could not force it open. With that I broke in a window which led us to a discovery of the undermentioned Goods, which was Seized and lodged in his Majesty’s Warehouse. Since which discovery was made by me, they knowing me by living in the neighbourhood, they have made it their Bufsinefs to watch for me to seek my Life on which Account I have been Oblig’d to fly for safety with my family of a Wife and five Small Children Which are quite destitute In a strange place and hope your Honors will take it into Consideration, We being in your Honors Service for these Eight years, whose Character will bear the Strictest enquiry into, on referance to Cap:tn Jane or any of the Officers I have served under, or John Keale Esq:r of London, who has known me for many [years] and had my Character from Capt:n Johns own Mouth. Your Petitioner hopes your Honors will take his Case into Consideration, And as in duty bound will ever pray.

John Thompson

N:B the Licquor when Gauged contained the following Quantity of: Rum 40 Gallons, Brandy 739 d:o, Geneva 2778, Wine [no amount entered]

To the Collector & Compt:r Penz:ce for their observations & report

By order of the Commifs.rs H Hutson

12th Decr[*]

Inevitable the Penzance officers were required to report their observations about Thompson’s claim, and they in turn referred to Captain John for his comments.

We beg leave to report to your Honble Board that the within Petitioner came to the Collector on the morning of the 11th June last, and informed him (with Capt.n John’s Compliments) that the Brigantine Lord Hood was then in Prufsias Cove discharging her Cargo. That the Dolphin could not get in to secure her, having been fired at repeatedly from their battery, and requesting the afsistance of the Officers from this place by land. Which was immediately complied with but without effect ‘till the Arrival of the Military. We cannot say any thing as to the Character of the Petitioner, having never seen or heard of him before. We have made every enquiry of Captain John about him and enclosed beg leave to transmit his answer. The Quantity of Liquor brought to His Majesty’s Warehouse in this port is as under, the remainder carried by Capt. Kinsman to the Excise Warehouse, the whole of which is humbly Submitted.

JS. Collector, JND/Cont.r

Brandy 90, Geneva 903 galls

Custom H.o Penzance, 31st Dec.r 1792 [*]Gentl:n, In reply to your enquiry respecting John Tomson I have to acquaint you for the Honble Board’s Information that he was a Mariner belonging to the Dolphin untill the 13th July last when for disobeying orders and refractory behavior he was dismifsed (his pretention to any particular Emolument from the Seizure at Prufsia (Alias Carters Cove) on the 12th June, more than as a Mariner belonging to the Dolphin, are improper & highly prejudicial to the Dolphin’s Crew – The Honble Board will find by my letter dated 6 July, thro’ the Custom House S;t Ives that John Tomson was then belonging to the Dolphin he was sent by me to you Gentlemen on the 11th June to inform you that the Dolphin had been fired on from a Battery at the said Cove and there by prevented from seizing the Lord Hood, a noted Smuggling Brigg, then in the Act of running her Cargo. And to request you would send the Officers of the Port to my Afsistance. You will therefore be pleased to inform the Honble Board of the Mefsage he delivered. I at the same time dispatched another Mefsenger to the Collector at Falmouth requesting he would send me such reinforcement as could be rose there, in Consequence thereof the [Fox] Excise Cutter Kinsman & Speedwell Custom House Cutter Hopkins both laying at Anchor in that Harbour, were ordered out, and a party of Soldiers dispatched by land, but the Smugglers being appraised of their Coming to my afsistance, sent a number of men on board the Lord Hood, in addition to he Crew, Set her Sails, Cut her hawser that was fastened to the Shore near the Battery & pafsed by the Dolphin in Defiance of every effort to prevent her. Nor was she overtaken till five hours pursuit & a run of sixteen Leagues. In the mean time the officers and Soldiers had joined near the Cove, When John Tomson whom I had left behind for the purpose of pointing out the Cellars, where he and the whole of the Dolphin’s Crew had seen the Goods lodged, made an Affidavit to the fact on which a search was made, Aided by the Fox Excise Cutter and the Seizure effected. John Tomson acting under my orders did no more than his duty. And I am fully convinced had any other of the Dolphin’s Mariners been sent instead of Tomson on this Service it would have been executed with equal exertion. Therefore I humbly presume it will appear to the Honble Board that Tomson is only entitled to share as a Mariner, And that the Dolphin, notwithstanding she was not directly on the spot at the time the Goods were taken into pofsefsion in consequence of the Chace. I trust the Honble Board of Customs and Excise will deem her the principal Actor in the whole Businefs and order the Contribution Accordingly.

I am Gentlemen – Your Most Ob:t Hum:le Serv:t, Rich: John Sen:r

Collector & Compt:r, Customs Penzance

28th Dec:r 1792 [*]

Of course Capt. John was anxious not to see his share in any rewards diminished by additional legitimate claims. He dismissed Thompson’s claim, but as Thompson was instrumental – if not key – in alerting the other parties, and in getting the magistrates to issue a search warrant, it might be argued that he was a principal in the seizure – albeit only carrying out the direct orders of his superior officer. Pointed observations on this incident were made by one of the local magistrates, the Rev. Edward Giddy JP, in a letter to Henry Dundas in which he confirmed John Thompson’s involvement with others.

Sir, On Tuesday last, John Julyan, an officer of the Customs at Penzance, applied to me for a Warrant in order to search some places in & about the Cellars belonging to Charles Carter in the parish of S.t Hilary, at Portloe & Port Trenalls Known by the name of Prussia’s Cove within the Port of Penzance, commonly Known by the Name of the Farmer’s Cellars, & other Cellars & Lofts within the said Cove, in which he Suspected that Brandy & other Spirituous Liquors were fraudulently concealed. He produced at the Same Time One John Tomson who made the following Declaration

That he belongs to a Revenue Cutter Commanded by Captn Richard John, & that on Sunday afternoon last he discovered a Brig coming up the Channel which he Suspected to be laden with Smuggled Goods, that the Said Brig proceeded to a Place call’d Prussia Cove, that a Boat was dispatch’d from the Cutter to observe what was doing by the Brig in the said Cove, & to prevent any smuggled goods being landed, that he was in the Boat, that he Saw a large Raft move off from the Brig laden with large Casks, & that he also Saw Casks on the Shore, that on the Boat approaching the Brig some shot were fired at it from a Battery on the Shore, & that some fell so near the Boat as to throw Water into it, that finding they could not prevent the landing of the Brig’s Cargo nor remain Safely in the Cove, they rowed off the Boat & proceeded to Marazion – He added the Battery also fired on the Cutter on its attempting to enter the Cove.”

Soon after the Murder committed at Scilly by James Dunkin I took the Liberty of writing to the Commissioners of the Customs, concerning Prussia Cove, & the pernicious Consequences of Suffering the Battery to remain there. At a very Short Notice 500 Tinners may be collected there to oppose any Seizure; the Guns have, before the present Instance, been turn’d against the officers of the Customs. Frequent Representations, I hear, have been made of this enormous Nusance –

As it is Suffer’d to remain the Smugglers now say Government has nothing to do with it; & that Carter has certainly as much Right to have a Battery for Defence, as Gentlemen for Ornament.

If it should be thought proper to make an Enquiry into this Matter, I apprehend the Collector & other officers of Penzance will give an exact Account of the Quantity of Liquor seiz’d, of the places in which it was lodg’d, of the Name & Proprietors of the Brig, wch is taken, of the Behaviour of the people of the Cove during the Time a party of Soldiers was on the Spot, & after it was under a Necessity of quitting it, through Fatigue & for want of Accommodations; & the Captain of the Cutter will of Course give an Account of the Firing from the Battery

I beg leave to refer to the Letter which I wrote to the Commissioners of the Customs. You will I flatter myself, Sir, be So good as to believe that a Sincere Regard to the Interest & Honor of Government is my only Motive for troubling you with this Narrative.

I have the Honor to be, Sir, your most obedient and most humble Servant

Edw: Giddy (Clerk), One of his Majsety’s Justices of the peace for Cornwall

The Right Honourable Henry Dundas Esq.r

Tredrea 16 June 1792 [*]

Justice Giddy’s position seems to have been ambivalent. On the one hand he was one of the more outspoken local magistrates, willing to make a public stand against smuggling. On the other he acts defensively of John Carter, particularly about his later offering to surrender to bail. Giddy was undoubtedly aware of most of the facts surrounding this and previous incidents, but he remains strangely reluctant to specifically name any of those involved. Later, when the Privy Council get involved in the issue of John Carter and his private battery, it was implied that the Giddys’ had failed to forward the necessary information to the proper authorities – which on the evidence seems far from the truth.

For reasons not immediately apparent the settlement of any resultant seizure rewards in favour of Captain Richard John and the crew of the Revenue Cutter Dolphin, was not resolved for some considerable time. Bureaucracy ruled. In September 1793 Captain John restated his claim, submitting his supporting evidence in an address to the Board of Customs.

No.9 ~ Marazion 24th Sept.r 1793 ~

Gentl:n, Pursuant to the Honble Boards orders thro: M:r Hutson dated 16th Instant, for me to state the ground and Merit of my claim on the seizure made at Prufsias cove the 11th of June 1792 = I have for the Honble Boards clearest insight to the businefs inclosed copies of such information & reports numbered from 1 to 8, as will I trust be sufficientlly satisfactory to their Honors to allow the Dolphin at least one third part of the whole seizure made by Excise & Customs at that time. Should the Honble Board require further proof of these facts I beg leave to refer their Honors to M:r Roger Ormond Mate of the Dolphin & the rest of Her crew, who are now at Deptford on board the Dolphin She being there under repairs. And I beg that you Gentlemen will Certify on this that the Officers from y.e out Port were sent to my afsistance in consequence of a Mefsenger I dispatched to you on the Morning of the said 11th June, respecting the Obstruction I had meet with then there can no doubt remain, but the whole force of sea & Land was collected by my exertion & the seizure made thro: that means

I am Gentlemen Your most Obe:t Humble Serv:t Rich:d John

To the Collector & Compt:r Customs : Penzance [*]Papers inclosed: [*]

No.1 My Letter to the Coll:r & Compt:r Falm:o craving a reinforcement dated 11th June 1793

No.2 My Letter to the Honble Board thro the Collector & Compt:r Customs Falmouth dated 12th June 1792

No.3 My Letter to the Honble Board thro: the Collector & Compt:r S:t Ives dated 6th July 1793

No.4 My Letter to the Coll:r & Compt:r Penzance dated 24th Oct:r 1792

No.5 Mr Letter to M:r Edsall Collector of Excise Truro dated 24th Oct:r 1792

No.6 My Letter to the Honble Board of Excise thro: M:r Esdall Collec:r of Excise Truro dated 13th Dec:r 1792

No.7 My Letter to the Honble Board thro the Collector & Compt:r Penzance dated 28 Dec:r 1792

No.8 My Petition to the Honble Board of Excise dated 29th Dec:r 1792See The Collectors & Compt:rs Letter No. 68: 23rd Aug:st 1793 ~ [&] 27th Aug.t

**

To the Solicitor (with former papers By order of the Commifs:rs – J T Swainson

I Submit that Capt:n John may be called on to state the Ground & Merits of his Claim –

J Earnshaw for M:r Cooper, 8th Sept:r 1793 ~

The Collector & Comptroller of Penzance are to proceed as submitted by the Solocitor returning these Papers By order of the Commifsioners 16th Sept:r ~ Hy Huston

We beg to transmit the annexed Letters to your Honble Board, which We have received from Captain John stating the ground and merits of his claim to the within mentioned Seizure & likewise to acquaint your Honrs that the Officers of this Port were sent to Prussias Cove in Consequence of a Mefsage received by the Collector from Capt. John on the 11th June 1792, otherwise they could not have received any information thereof the whole of which is humbly submitted

J Scobell Coll.r, J Nichols D/Com.r

Custom House, Penzance, 28th Sept.r 1793 [*]

The existence of the battery having gone almost unnoticed in the original reports submitted in June and July 1792, the Commissioners of Customs still did not pick up on its presence, and the above complete re-iteration of the facts seems to have had little effect. The Board seem to have been far more concerned with the immediate point in question – the equitable distribution of the seizure rewards. The question of the private battery at Prussia’s Cove was to come to a head again in February 1794, though the guns mounted there were then stated to be four-pounders. Throughout its supposed existence there is no congruity over the number and size of the cannon. Perhaps this was due to the fact that the guns were regularly being changed as privateers outfitted by the Carter Brothers were commissioned or de-commissioned – all depending on the current state of international hostilities. This was no fixed battery in military terms, but was an ad-hoc battery set up as and when required.

Whatever the outcome of the respective rewards claims, this encounter with the smugglers at Prussia’s Cove was accompanied by the seizure of the Lord Hood at sea shortly after she put off from the cove. And – given that this was the second time the Lord Hood was seized and detained, it seems baffling to me that she did not then suffer the full due process of law and end up ripped to pieces. However, after a long period of detention, after due process of law the vessel was restored to her owners ‘at a valuation’ rather than condemned.

But to return to the events of June 1792. Not immediately apparent from the Penzance Custom House correspondence was the ensuing arrest and trial of Charles Carter. It would appear that this was because Charles’ prosecution was undertaken by the Commissioners of Excise – whose Officers also claimed the lion’s share in the seizure of contraband spirits which had been carried off by them in the Fox, to the Excise warehouse at Falmouth. The cause came to trial on February 21st 1793, when ‘an information’ against Charles Carter was presented by the Attorney General:

‘… to recover treble the value of the following goods which our Case contends were seized in a Cave in a Cellar belonging to the Defendant namely 649 Gallons of Brandy 40 gallons of Rum 1874 gallons of Geneva and 2 pipes of Wine Gentlemen the questions of fact which you will have to try will be whether the Defendant was concerned in unshipping these articles before the payment of duties or whether these articles came to his hands unshipped without payment of duties or whether he harboured these articles being unshipped and landed without payment of duties.’ [*]

Some 112 pages of evidence later, the outcome of the cause hinged on some questionable transactions about the ownership of the cellars in which the contraband goods were discovered. Not convinced by the evidence to the contrary, the jury concluded that Charles Carter was indeed the current owner of the cellars, and found for the Crown on the third count in the sum of treble the value of the seized goods – £1,469 12s.

Much was made about the presence of the battery guarding Prussia’s Cove, and the judge appears to have thought it might have been an officially sanctioned battery, asking ‘Is there any guard-house or blockhouse or any thing of that sort? Government seldom leave guns to take care of themselves I believe.’ [*]

Not surprisingly defendant Charles Carter did not give evidence, the risks were too great for him to take the stand. But neither did John Dunkin, who was present in the court. Considering the Lord Hood’s key role in events this fact was remarked upon by the Crown prosecutors. But Dunkin and the Lord Hood were also under trial at the same Exchequer sessions, and I can only assume that Dunkin could not afford to risk his cause by giving evidence in this one!

Details of this second trial have yet to be discovered. I had hopes that a search of CUST 103, would turn up trumps! But it did not, this source relating to Excise causes, while on this occasion the Lord Hood appears to have been held by the Customs Commissioners. – and I have not discovered a Customs equivalent series of trial reports. All we do know is that there was a great deal of preparatory work in Cornwall prior to this trial.

When Louis the Sixteenth was executed on Monday 21st of January, 1793, and hostilities with France were subsequently declared, the Lord Hood – while detained – was still entered on the St. Ives Register of shipping. There remained considerable legal problems with obtaining her release. John Dunkin (presumably still her notional principal owner) was now very active in trying to secure her release from the Customs Commissioners, and consulted frequently with Helston attorney Christopher Wallis. about this – as the latter noted in his journal:

1793

January 5th Attended Mr John Dunkin relative to Treluddra’s wines, the petition rejected, and Aff.s of the Agent in the Court of Exchequer informal, and contriving to amend.

Attended Mr John Dunkin relative to the claim of the Lord Hood Brigantine carried into Falmouth, ab.t Pet.n to have her out on Bail being given for appraisement value &c. &c.

10th Drawing Aff.t of Mrs Treluddra of Penzance, that her husband was at Sea, that he had made a claim of wines &c. –

Drawing Pet.n of John Dunkin to Commrs Customs requesting to have the Lord Hood Brigantine delivered on Bail

31st Attending John Dunkin about the Lord Hood, drawing notices to put in Bail for Customs &c.

February 7th At Marazion by appointment and in pursuance of notice given Mr. Scobell Collector of Penzance, taking recognisance for Bail in the Lord Hood against The King, when Mr Odgers and Self took the Bail in the presence of Mr Scobell – on behalf of Mr John Dunkin the Claimant.

With Mr John Dunkin about Treluddra;s wines – Lord Hood – Liberty & Cargo.

12th Attended Mr John Dunkin relative to Lord Hood, Liberty and consulted thereon, and drawing Petition to Commissioners of Customs to have Lord Hood on appraised value &c.

16th Attended John Dunkin relative to Lord Hood, Liberty, and several other matters, he set off for London, this Evening. [*]

There were three different causes in play here. The first was the true ownership of wine found in the cellar of the Dolphin Inn, Penzance – prop. John Treluddra – which cellar adjoining one owned by John Dunkin. This cause was tried in July 1794, when the wine was deemed to belong to John Dunkin with a verdict for the King – but unfortunately no details of the accompanying sentence were noted in the trial record.[*] The other two causes related to the restoration of Dunkin’s vessels Lord Hood, and Liberty.

Bail for the Lord Hood having been given by Wallis and Odgers, the vessel was restored to John Dunkin. Within a couple of months of her restoration, on 17th of April, 1793, John Dunkin successfully acquired a Letter of Marque for the Lord Hood to cruise against the French, Essentially a licence to take prizes from an enemy, it was prohibited to grant any such to ‘known smugglers,’ but Dunkin had never been convicted of smuggling.

Licensed to take reprisals from the French, she was authorised to carry 14 guns and a crew of 70 men. Despite her official St. Ives registry, in her Letter of Marque declaration she was still described as being ‘of Penzance.’ However, once restored to her former principal owner she did not long remain on the St. Ives Register, being transferred back to Penzance on June 12th, 1793. [*] Her owners were now given as John Dunkin and John Ellis, Penzance merchants – Ellis being the same Penzance merchant who was standing surety for John Scobell, the Collector of Customs at Penzance, for due performance – and possibly the same John Ellis, as was convicted in the Court of Exchequer of ‘cyder’ offences in July 1792. [*]

William Michell was again in command of the Lord Hood, and some days earlier, on the 5th of June, while technically still registered at St. Ives, the Lord Hood had sailed from Penzance on a privateering cruise. A cruise that supposedly proved successful for her owners if not for her crew! I say supposedly successful because her capture was a re-taken English vessel, which has not yet been identified, nor the outcome of any prize/salvage action.

On Wednesday the 5th instant sailed from Penzance, the Lord Hood privateer, of 16 guns and 70 men, commanded by Capt. Michell, and the Sunday she returned with a ship of 400 tons, which she took within two hours sail of the coast of France; she is an English vessel, laden with wheat and flour, and would have been a desirable prize to the French in the present time of scarcity, had she not been retaken. The Lord Hood, meeting with a man of war in the Channel, had full one-half of her men pressed. [*]

The one of the naval vessels that received pressed hands from the Lord Hood on this occasion was HMS Lowestoft. Although the above newspaper account reported that a full half of her crew were seized, only 21 men have been found entered in the Lowestoft’s pay books on June 8th. They were:

| No. | Name | Quality | Age | Where born |

| 285 | William Sleeman | AB | 45 | Mount’s Bay – made up to Sailmaker’s Mate on July 1. |

| 286 | Richard Roberts | Ord | 27 | Mount’s Bay – made up to AB. on April 2nd 1794. |

| 287 | James Tonkin (1) | AB | 22 | Mount’s Bay |

| 288 | John Sullivan | AB | 29 | St. Just – made up to Sailmaker’s Mate on July 1. |

| 289 | John Burgan | Ord | 25 | Mount’s Bay – made up to AB on April 2nd 1794. |

| 290 | Ralph Corin | AB | 40 | Penzance |

| 291 | William Harry | AB | 32 | Newlyn |

| 292 | James Tonkin (2) | AB | 23 | Mount’s Bay |

| 293 | Francis Stephens | AB | 36 | Marazion |

| 294 | John Bawden | AB | 42 | Mount’s Bay |

| 295 | Noah Cazeley | AB | 24 | St. Just |

| 296 | John Maddern | AB | 20 | Mount’s Bay |

| 297 | John Curnow | AB | 20 | Mount’s Bay |

| 298 | William Kelynack | AB | 25 | Penzance |

| 299 | George Wills | AB | 24 | Mount’s Bay |

| 300 | William Choke | AB | 28 | Mount’s Bay |

| 301 | William Maddern | AB | 36 | Mount’s Bay |

| 302 | John Mennear | AB | 20 | Falmouth |

| 303 | William Johnson | AB | 30 | Plymouth – made up to C’s [?] Mate on July 6. |

| 304 | John Oliver | AB | 40 | Marazion |

| 305 | John Kelynack | AB | 20 | Penzance |

About half of these men had ‘tickets’ indicating that they had served in the navy previously, and John Oliver was also wanted on other smuggling charges from an incident in 1792.

As stated, the recovered English vessel has not yet been identified, and the Lord Hood’s Letter of Marque should have ensured her crew’s protection from impressment. However, the majority of Royal Navy officers held privateers and their crews in contempt – though they recognised them as prime seamen. They regarded privateers as little more than licensed pirates – though Naval Officers were not averse to receiving prize-money themselves. So we find that while the crews of privateers were officially protected from impressment, whenever such vessels were ‘homeward’ bound, Naval officers felt little obligation to honour the letter of the law. They were ever inclined to seize good hands whenever the opportunity arose, and argue about it later. Back in port, a replacement crew was enlisted with apparent ease, and the Lord Hood sailed on another privateering cruise, but some of the new crew fared little better than the former.

Last week arrived at Penzance the Lord Hood privateer, from a cruise of three months, in which she had taken nothing. In her former cruise half her crew, consisting of 60 men, was impressed; and towards the conclusion of this, she was relieved of 16 in the Bay of Biscay, by one of our frigates upon that station. – The day before her arrival she met with a heavy gale, which carried away her main mast, forced some of the guns to be thrown overboard, and otherwise damaged her. She is, however, about to be completely refitted for the same service. [*]

The ‘relieving’ frigate is not named on this occasion, and the fact of her having cruised for three months without taking a prize suggests that the Lord Hood was back to her old tricks of free trading, and the pilchard export season was now at hand. Despite the asserted intent reported in the newspaper, her owners seem to have had enough of privateering. With the war many months old the opportunities for snapping up easy prizes had significantly decreased. Her gale damage repaired the Lord Hood was sent out on a normal trading voyage, again carrying a cargo of salt-cured pilchards to Naples.

Meanwhile, over six months after Charles Carter’s trial, Captain John of the Dolphin had still not received an answer to his petition for a share in the seizure awards arising from the events at Prussia’s Cove on 11th & 12th of June 1792. Now petitioning as the ‘late commander’ of the Dolphin [had he been beached?], in March 1794 he submitted another claim in the hope of a fair settlement award. –

To the Honorable the Comm:rs of His Majesty’s Customs

The Humble Petition of Rich.d John late Comm.dr of the Revenue Cutter Dolphin.

Sheweth,That your Petitioner hath repeatedly represented to your Honors the transactions & cause of a Seizure made at Prussia’s Cove in Mounts bay the 11th & 12th June 1792, assisted by the exertions of Mr. Scobell Collector at Penzance, and Mr. Pellew Collector at Falmouth, in their dispatching the Officers from Penzance, a party of Soldiers from Truro, & the Fox Excise Cutter from Falmouth, at your Petitioners request, by special Messengers to his assistance, when fired on from a Battery of Large Cannon mounted there in attempting to board a Brig known to be the Lord Hood in the Act of running her Cargo and thereby prevented from making the Seizure alone. As hath been more fully set forth to your Honors in your Petitioners Letter dated 24th Sep.r last, inclosing eight Copies [of] different Letters & Petitions on the matter of said Seizure. Your Petitioner therefore most earnestly pray your Honors will be graciously pleased to interfere in the distribution, of the Officers Share / part of which lies in the hands of M.r Edsall Collector of Excise at Truro, & part in the hands of the Collector & Comptroller at Penzance, and not suffer the Commander of the Fox, or any other pretender to greater merit than they deserve to share – more than a just proportion, because the Seizure was returned in their separate names to the prejudice of your Petitioner & his deserving Crew.

And your Petitioner as in Duty bound will ever pray.

26th March 179427 Do. rec.d