1779 – fear of invasion

12 September 2021

In search of Cockshot designs

19 October 2021Hilary Tunstall-Behrens looks at an incident from HM Sloop Fairy’s later career which is oddly similar to an account in Fairy’s log book for 1795.

As a practical seaman in my younger days, while researching the myth of H.M. Revenue Cutter Fairy coming under fire from John Carter’s cliff-side battery of cannon, I was taken by this further incident in the life of H.M. Sloop Fairy.

In 1794, nearly ten years after her spell on anti-smuggling patrol duties in Mount’s Bay and the Chops of the Channel, Fairy was returning to England. Under the command of Captain Richard Bridges Esq., and navigated by Thomas Sinclair, her Master, the sloop had recently completed a spell of duty in the West Indies with her commander under a cloud. Leaving Guadaloupe for England on 26th October 1794, she had arrived at Liverpool on 24th December, where Bridges was ordered to proceed to the English Channel in Fairy, and report to HMS Asia, at the Nore. Here Captain Richard Bridges was to be tried by Court Martial, having been accused by his Second Lieutenant, William Crooke in letters to Admiral Jarvis, of four serious Counts:

Of having behaved in a most tyrannical and oppressive manner, endeavouring to set his Officers at variance ….

… constantly abusing his Officers before the whole ship’s company.

Frequently coming aboard drunk …

… and beating and injuring his West Indian servant· cruelly when he came aboard drunk.

Lieut Crooke had been threatened by Capt Bridges that he would have to quit the ship or go to sick quarters, which he refused to do. Accordingly, since leaving the West Indies Lieut Crooke had been confined to his cabin, a marine sentry constantly on guard, while the Master, Thomas Sinclair, had to stand duty in his place as an officer of the watch for the whole voyage home.

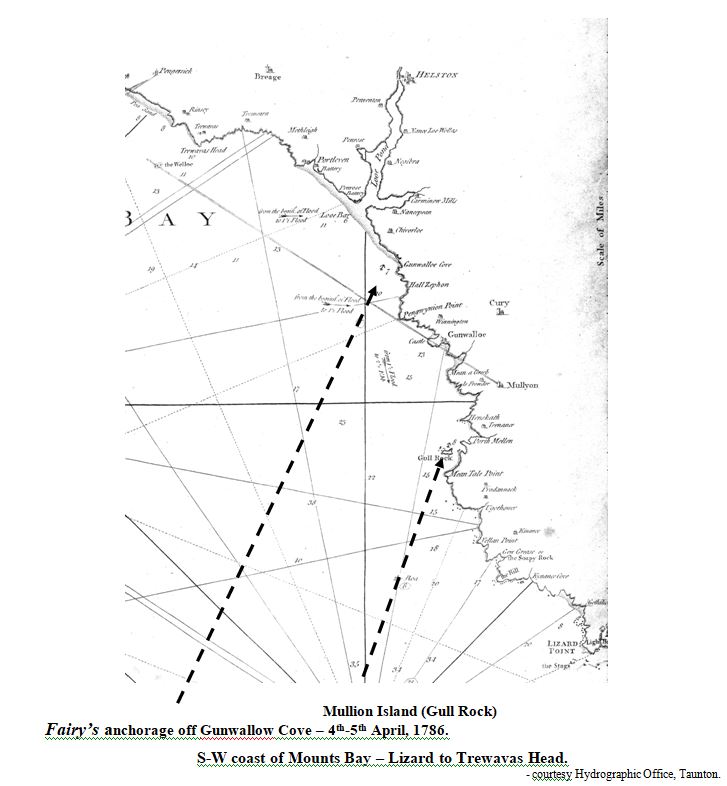

On her way round from Liverpool, on 27th December 1794, HM Sloop Fairy put into Milford Haven, setting sail again for The Nore on 21st January under conditions of heavy gales and a great fall of snow. Her captain was in no great hurry to reach his destination, and a couple of days later they hove too in Mount’s Bay.

The account of what followed next is taken from-the Captain’s and the Master’s logs – mainly from the latter as more informative, even though it is harder to read. A sea hardened warrant officer, responsible for ship handling, Thomas Sinclair of the Fairy proved himself a fine professional seaman. His competent actions brilliantly saving the ship from certain destruction. Surprisingly, for a hardened seaman, he often ventures to express himself in a remarkably poetic and haunting vein.

Surprisingly there are two extant Captain’s logs, one a rougher deck log, and the second one written up a little after the conclusion of events described with regard to this episode. The latter is very much fuller, but still, in contrast to the Master’s log, it does not show a close grasp of the situation, nor a full appreciation of the only solution as it developed – but Bridges may have been preoccupied with his forthcoming Court Martial. Whatever, it is evident that the Master was the Officer who was in control during this emergency.

Seeking a Channel Pilot, either late on the 21st or early on the 22nd they ‘Bore up for Mount’s Bay wind ENE, and anchored in Gwavas Lake off Newlyn.’

Having picked up their pilot, on 22nd January an attempt was made to sail out of Mount’s Bay and round the Lizard, but this move failed and she returned to anchor. On the 23rd conditions worsened and there was a strong gale of wind from SSE – right into Mount’s Bay. T’gallant masts and topmasts were lowered, and the lower yards were brought down on deck to ease the ship’s heavy motion. Violent jerky motion which was threatening to start her anchors from their holding ground, or part her cables.

26th’ . . . strong gales and squally wind SSE to WSW,’ the best Bower anchor was let go and the whole cable veered on the small anchor. The gale increased and the topmasts are struck. At 9 a.m. the wind moderated and the best bower is hove up, and finding the cable much chaffed it is cut off and bent afresh.

In the early part of the 27th there are still strong gales and heavy rain, then in the latter part it moderated, but became very thick with mizzling rain. At 9 a.m. hauled up lower yards and topmasts and the t’gallant masts, and hove short on the small bower. Having also received on board a delivery of 533 lbs of fresh beef, in the afternoon they prepare for sea etc.

28th January, the first part of these 24 hours fresh gales & cloudy, the middle nearly calm with thick weather, and mizling rain. Another attempt was made to leave Mounts Bay. At 1 p.m. weighed set sail under double reefed tops’ls with a fresh Gale. W by S. at 2 p.m. more moderate , out reefs and up Topgall’t yards but a heavy swell. 4 p.m. quite calm & the visibility exceeding thick, being a Westerly tide (ie Ebb Tide) I did not think proper to anchor .

At 10 p.m. it was still calm, but there were heavy seas rolling in, and having drifted into 20 fathoms of water there were no signs of either wind or clear weather.

Came to with the best bower anchor, veered two thirds of a cable. At half past 11 p.m. parted the Best Bower about three fathoms from the anchor, let go the Small Bower when the ship had drifted into 15 fathoms hard ground and a heavy sea, at 1 a.m. a Breeze springing up from the NW and clearing a little found the ship within little more than two to three cables length.

This was the Master’s opinion, but the Captain writes:

… a ¼ of a mile off the rocks at Gunwalloe Point, it then coming to blow very hard & expecting the Small Bower to part every moment when nothing could have saved the ship.

This was a perilous situation, for any vessel, caught on a lee shore, in a gale and heavy seas, under that notorious skirt of vicious cliffs, running from ‘Halsferran’ (Halzephron) Cliff, through Poldhu Point, Mullion, Predannack Head, Kynance, Pentreath, Crane Ledges to the Lizard. A sloop of Fairy’s build, even under good sailing conditions, would be lucky to make good a course closer than 40 degrees to the wind. In these really frightening conditions, in total darkness, with a heavy SW swell and breakers, and within hearing distance of a fatal lee shore, only the classic manoeuvre of ‘Club Hauling,’ could possibly save them. It was a desperate gamble. See below for a description of ‘club hauling,’ taken from an early Seamanship Manual.

It was now thought most expedient to make sail and cut the cable, there being a chance of weathering the rocks – at this point the Master’s Log is more specific and precise:

At a quarter past midnight the wind, at that crucial moment shifted to the SW and blowed with a great violence … got a spring from the starboard quarter on the cable. At ½ past one having got the topsl’s set, when the bow fell off the wind cut the cable within 4 fathoms of the splice and at the same time making what sail the ship could suffer, and not without difficulty cutting the spring we dragged off the rocks very well … the ship before she got headway was in 4 fathoms of water …

That is in only 24 feet, and the Fairy drew at least 13 ft aft when deep laden, leaving only 10 or 11 feet of water under her keel. But in the troughs, with the sea that was running, it must have been touch and go. Clawing off the land, in Mr Thomas Sinclair ‘s own words – ‘The ship steering a Channel Course as daylight haunted the North, the weather conditions were heavy gale, we made the Channel clear of the Lizard’.

On their passage up Channel, on February 4th they brought to a Dutch Ship De Vraue Susannia Mariea, with a valuable cargo, which must have proved some small consolation for her anxious commander.

After putting in to clear Quarantine, they passed through the Downs to anchor at Blackstakes, the Nore. Their voyage was ended.

On the 17th February, 30 members of the Ship’s Company with the Officers attended the Court Martial of Captain Bridges aboard HMS Asia. But it was not until March 10th that the court pronounced its verdict and sentence.

Captain Bridges was pronounced guilty in part on the third charge, and guilty in that he constantly abused his Officers before the whole Ship’s Company, in an unofficer-like scandalous and ungentlemanlike manner; and of the fourth charge that when coming aboard from ashore drunk, he either abused his officers or beat his servant in a cruel manner.

Captain Bridges was duly dismissed His Majesty’s Service. Lieutenant William Crooke was honourably acquitted.

For the last time the Captain’s Log was duly signed, one can imagine not without considerable pain and chagrin, by Captain Richard Bridges, his final act on leaving the Navy in disgrace.

A Treatise on Practical Seamanship with Hints and Remarks … by William Hutchinson, Mariner, and Dock Master, Liverpool. Printed 1777 (which may be the earliest written treatise on Seamanship).

‘On drawing near to danger, or making a Landfall.

‘In spite of taking every precaution I have experienced very narrow escapes on our own coast, it was my case in a ship coming from Leghorn and we just got a glimpse of the South side of St Mary’s Scilly Island and concluded it was the Lizard point which we had seen and ordered with confidence a Channel course, but our mistaken situation occasioned the ebb tide to take the ship on the starboard bow, which steered us insensibly into the bottom of Mounts Bay: about midnight we were surprised with broken water and land extending as far as we could see on our starboard bow, when carrying topgallant sails with a fresh gale quartering at S.W. and large swelling waves from the main ocean quartering right into the bay.

‘The hurry we were in to exert our utmost endeavours at this critical moment may be judged from our dangerous situation; we had our small sails to take in, and our tops’ls to· get down, before we could bring the ship by the wind to lay her head from the nearest breakers, and we had the main and foretops’ls to close reef, and the topgallant yards, etc to get down, when we had not room to stand above a quarter of an hour upon a tack clear of the breakers. But putting the ship in stays which she refused and then wearing her round, by boxhauling frightened the passengers from their prayers in the great cabin and they all came on deck thinking we were running the ship on shore.

‘We thus managed by boxhauling; as soon as we perceived the ship ceased from coming about in stays, we hauled the foresheet close aft again, trimmed the heads’ls flat whilst the sails were shaking, and hauled about the main and main topsail the same as if the ship had stayed, hauled up the mizzen and kept the helm hard a lee, by which the ship getting great stern-way turned short round upon her heel, till she filled the main and main top sails the right way, we then shifted the helm hard a-weather, when the ship got headway with the sails trimmed which brought her readily round, with little loss of ground, by these means in about twelve hours we turned to windward so far off the lee shore as to weather the Lizard.’

In view of the account in thew Fairy’s log books in January 1795, the example of a vessel caught right under the cliffs in Mounts Bay on the Lizard side is so nearly the situation in which the Fairy had found herself, as to be uncanny, although the two manoeuvres are different. The example given on page 131 of this seamanship book is ‘Box Hauling’, the vessel never dropped her bower anchor, whereas the Fairy succeeded in ‘Club Hauling’, attaching a spring to the bower and then cutting the bower cable, letting the spring leading from the counter, attached to the bower anchor holding the stern up to the wind and as the bow fell off, cutting the spring. Of course this rarely experienced feat of seamanship means that the anchor and ground tackle is lost and abandoned on the seabed.’

In view of the account in the Fairy’s log books in January 1795, the example of a vessel caught right under the cliffs in Mounts Bay on the Lizard side is so nearly the situation in which the Fairy had found herself, as to be uncanny, although the two manoeuvres are different. The example given in this seamanship book is ‘Box Hauling’, the vessel never dropped her bower anchor, whereas the Fairy succeeded in ‘Club Hauling’, attaching a spring to the bower and then cutting the bower cable, letting the spring leading from the counter, attached to the bower anchor holding the stern up to the wind and as the bow fell off, cutting the spring. Of course this rarely experienced feat of seamanship means that the anchor and ground tackle is lost and abandoned on the seabed.