During the English Civil War Cornwall remained loyal to the Royalist cause. Both the Queen, Henrietta Maria, in 1644 and in 1646, Charles, Prince of Wales, were forced to flee the kingdom from Cornwall. After sheltering in Pendennis Castle at Falmouth and despite the attempts at interception by the Parliamentary navy they were able to make their escapes by sea.

In another of her pieces about Falmouth, volunteer Linda Batchelor explores the background to the Royal Escape.

Henrietta Maria

This letter is to bid you farewell. I am giving you the strongest proof of love that I can give; I am hazarding my life, that I may not incommode your affairs. Adieu, my dear heart.

Green Letters of Henrietta Maria Henrietta Maria to Charles 9th July 1644

In July 1644 in the midst of the Civil War, Queen Henrietta Maria wrote this letter from Truro to her husband, King Charles. After leaving Exeter to escape the advancing Parliamentary army she had made the journey through Cornwall and was about to leave England by sea for France from Falmouth. She was never to see her husband again.

The Queen was thirty four years old and a month before writing this letter she had given birth to her ninth child in Bedford House, Exeter on 16 June 1644.1

Her baby daughter was healthy but the Queen was suffering with severe pains in her limbs which at times caused paralytic seizures and various other symptoms such as the loss of sight in one eye. Despite her condition the Queen felt she must leave the country as soon as possible to avoid capture and in order to protect her husband and his cause. The Earl of Essex and the Parliamentary forces were pressing towards Exeter, after relieving the siege of Lyme, and Henrietta Maria feared her capture would compromise the King’s position.

The Queen had been born Henriette Marie de Bourbon in Paris in 1609, the youngest daughter of the French King Henry IV and his wife Marie de Medici. She was married to King Charles in 1625 shortly after his accession to the throne of England. Despite a difficult start to the marriage it became a supportive and loving partnership which remained strong throughout and only came to an end with the King’s execution in January 1649.

The Civil War between the supporters of the King and the supporters of Parliament had finally begun when Charles raised his standard in Nottingham in August 1642. At the time Henrietta Maria was in Holland with their eldest daughter Mary, Princess of Orange, and had begun raising funds and support in Europe for the Royalist cause but was impatient to return to England. She landed at Bridlington under bombardment from Parliamentary ships in February 1643 and after considerable delay the King and the Queen were reunited in July at Oxford where Charles had established his court and headquarters. Although the King’s cause was proceeding well in the north and south west of England, Parliament controlled London and the south east. On the surface court life continued as usual but during the autumn and winter the King and Queen spent together in Oxford the war continued with no end in sight. By the new year the Parliamentary cause was rallying. New forces were being raised in readiness, Oxford was under threat and the Queen, now expecting a child, was fearful of being taken by the enemy and the consequences that posed for the king.

The decision was taken that Henrietta Maria should leave Oxford and go to the west country where if necessary it would be easier for her to make for France. Her journey began on 17 April when she left the city with her attendants and an escort of cavalry. Her husband and their two eldest sons, Charles and James, rode with her to Abingdon, staying at Barton House, before their final parting the following day. From Abingdon the Queen travelled to Bath and then through Devon to reach Exeter by 1 May where she took up residence in Bedford House. The house, close to Exeter Cathedral was the west country town house of William Russell, Earl of Bedford at that time a supporter of the Royalist cause.

The Queen who had been suffering with pains in her limbs throughout the previous winter was now extremely ill which prompted the King to beg his elderly physican ‘Mayerne, for the love of me, go to my wife’, to attend her in Exeter.2 Help was sent also from the Queen’s sister in law the Queen Regent in France and it is probable there were negotiations underway at this time for Henrietta Maria’s eventual flight to France. The Queen gave birth to a healthy baby on 16 June but her symptoms persisted causing serious concern for her life. With the Parliamentary forces advancing on Exeter, just a fortnight after giving birth and still suffering severe ill health, Henrietta Maria set out for Cornwall. Her newly born daughter had been left behind in Exeter probably considered as being too frail for the journey and entrusted by the Queen to the care of her lady in waiting and friend Anne Villiers, Lady Dalkeith.3

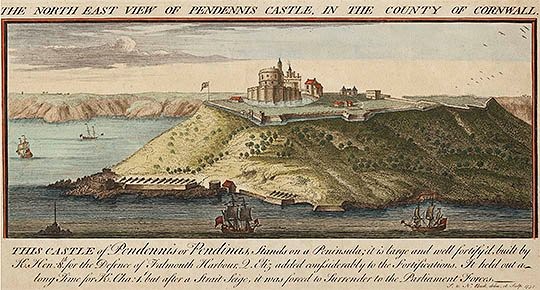

The Queen’s party were making for Falmouth. ‘The Queen is this day gone towards Falmouth, intending to embark herself for France’ her secretary Henry Jermyn had written to George Digby on 30 June.4 Cornwall was in royalist hands and Falmouth was one of the most valuable royalist ports supplying arms and munitions for the cause and allowing trade and passage to and from the continent. It had the important anchorage of the Carrick Roads in the deep estuary at the mouth of the river Fal and was protected by the garrisons of Pendennis and St Mawes castles. The castles had been built in the reign of Henry VIII as artillery forts to protect the Carrick Roads. Pendennis, the larger of the two, on its rocky headland with an elevated position overlooking Falmouth was perfect for defence both from the land and the sea and the manor of Arwenack, seat of the Royalist Killigrew family, was nearby. Falmouth offered an ideal point of departure for the Queen’s escape.

The Queen continued to suffer throughout her journey to the west. She was carried in a litter and her party’s progress was slow. By 9 July she had reached Truro in the west of Cornwall and wrote her letter of farewell to the King before travelling on to Pendennis Castle and Falmouth where a small fleet of ten Flemish ships were awaiting her anchored in the Bay. The Parliamentary authorities had control of the navy and were aware that the Queen was planning to escape from Royalist-held Pendennis. The Parliamentry naval commander Admiral Robert Rich, Earl of Warwick, had eight ships patrolling the waters of the South West and intended to prevent any flight. On 11 July he wrote to the Committee of Both Kingdoms informing them that he had despatched three of his ships under Vice Admiral William Batten to keep watch on Falmouth.5 It was William Batten who had commanded the attack on the Queen when she had landed at Bridlington in 1643.

Henrietta Maria had only a short stay at Pendennis Castle and with the Parliamentary ships in close proximity it was imperative to leave for France as soon as conditions allowed which was Sunday 14 July. She embarked with her companions on board the Dutch ship George and the small fleet set sail for France soon pursued by the Parliamentary squadron. The Queen ordered the captain to destroy her ship rather than allow her to be captured but the Dutch ships equipped with oars were faster than

their pursuers and were able to keep ahead. Nevertheless the English came close enough for Vice Admiral Batten in The Constant Resolution to fire a number of shots and the pursuit continued as they neared the Channel Islands. More shots were fired from the Warwick off Jersey some of which hit the rigging of the George but the Queen’s ships began to gain distance and as they approached the French coast at Dieppe a number of ships appeared. Unable to distinguish the nature of the ships Batten reluctantly called off the action and the Parliamentary squadron withdrew unable to prevent the Queen’s escape. The Earl of Warwick informed the Parliamentary authorities on 17 July that they had been denied their prize.6

Although the weather closed in the Queen’s ships were able to land near Brest and the party were able to disembark to a somewhat difficult and unannounced arrival. Soon however she was welcomed

to France with warmth and care and she was able to report to Charles in a letter of 10 August that despite the fact that she was still unwell she was safe, being treated with great kindness and sympathy. Later, on her return to Paris she joined the French court where she was made most welcome.

She continued to support Charles by raising arms and money for the Royalist cause and always hoped that she would be able to be reunited with him in England. This hope would never come to fruition and would end with his execution in 1649. She remained his widowed Queen for the rest of her life. Over time she was reunited with her children and although she lived in France for the next sixteen years she was able to return to England when her eldest son Charles II was restored to the monarchy in 1660.

Charles, Prince of Wales

In August 1642 Charles, Prince of Wales and his younger brother James were with their father the King when he raised his standard in Nottingham. At that time the Queen was in Holland with their eldest sister Mary and their youngest siblings were in the hands of Parliament in the south east of England.7

Charles had been born in St James’ Palace in London on 29 May 1630 the eldest surviving son of King Charles and Queen Henrietta Maria. He was a strong and healthy baby who continued to thrive throughout his childhood. As an adult he grew tall, over six feet in height or as he was described by wanted posters when on the run from parliamentary forces, ‘a man two yards high’. He was also required to face a number of other vicissitudes in the years to come as a consequence of the civil war.

After war was declared he and James accompanied their father on campaign and were present at the first major engagement of the war at Edgehill in October 1642. The King then set up his headquarters in Oxford where they were joined by the Queen. They were together until Henrietta Maria left for the west in April 1644 and made her escape from Cornwall to France.

The fortunes of war continued to ebb and flow for both sides over the next year but by 1645 the tide was turning against the King. Parliament had established its New Model Army and had set its sights on the Royalist bastions in the west. The King appointed Charles as titular Captain General in the West and set up a new Council to advise him and represent the King in the West. On 4 March, therefore, Charles left Oxford for Bristol with Sir Edward Hyde and Lord Hopton and their troops. Echoing the earlier parting of the King and his wife, the father and son would never see one another again.

Charles spent the next few months in the area around Bristol with time in Bridgewater and Barnstaple. It was there that Charles received the news of the Royalist defeat at Naseby on 14 June and his father’s retreat into Herefordshire and Wales. The Royalist cause in England was virtually lost. By July it became clear that Bristol was no longer safe for the Prince. General Fairfax and the New Model Army were advancing into Somerset and Charles and his advisors were forced to leave Bristol and move further west throughout the autumn.

The King was concerned not only for the Prince’s safety but believed that if he was captured his presence could be used as a threat against the monarchy. In letters to his son the King proposed a variety of refuges including France, Ireland, Scotland and Denmark. In one such letter he ordered that if the Prince was in danger of being taken by the rebels he should proceed to France and place himself under his mother’s command. In another that the prince should make for Denmark. Henrietta Maria also wrote urging that he should join her in France.

That time came in early February. On 16 February The Royalists under Lord Hopton were routed by Fairfax and Cromwell at Torrington in the final action of the campaign. The remains of the King’s Army in the West fell back into Cornwall. By 17 February Prince Charles and his Council had retreated to Truro and then to Pendennis Castle at Falmouth. The Castle was in loyal Royalist hands, in a strong defensive position and there was hope the Prince could remain there in safety for some time. The Prince and the Council were unhappy at the thought of the Prince leaving the kingdom for France but it was proposed that he should go to the Scilly Isles or Jersey as they were still in Royalist control and British soil.

The Prince remained at Pendennis until March whilst arrangements were made for his departure from the mainland. The plan was hastened by the news that General Fairfax had advanced into Cornwall and had entered Launceston by 25 February and Bodmin by 2 March. The Parliamentary navy also had twenty ships patrolling the south west coast. Furthermore intelligence had been received of a plot concerning Charles which was ‘a design for seizing his person’ and handing him over to the Parliamentary forces.

On the night of Monday 2 March, therefore, Prince Charles boarded the frigate Phoenix to leave Cornwall for the Isles of Scilly, twenty eight miles south west of Land’s End and the Cornish mainland. He was accompanied by Edward Hyde, John Colepeper and the Earl of Berkshire. Charles landed at St Mary’s in the afternoon of 4 March having taken the helm of the ship for some of the voyage. He was followed later by the rest of his retinue. Charles was lodged in Star Castle but there was limited accommodation for most of the party, fuel was scarce and food was short and Colepeper was dispatched to the Queen in France for money and supplies.8

The position became increasingly difficult and dangerous for the Prince and by 15 March Lord Hopton had agreed the surrender of Cornwall to General Fairfax at Tresillian Bridge near Truro. However, the Royalist garrison of Pendennis Castle which had recently housed Prince Charles refused to surrender. The garrison under Sir John Arundell withstood a five month siege with bombardment from the land by Parliamentary forces under Colonels Fortescue and Hammond and a blockade by sea from the Parliamentary navy under Vice Admiral Batten. The garrison was finally forced to surrender through near starvation on 15 August but were allowed to leave with honour with their drums beating and standards flying, the penultimate Royalist fortress to surrender.9

Both the King and the Queen continued to urge for Charles’ removal to France but the Prince’s advisors favoured Jersey. Charles arrived there in mid April, having avoided the Parliamentary fleet which was dispersed by a storm. He was aboard the Proud Black Eagle, a ship of 160 tons with twenty four guns, captained by Baldwin Wake. Once again Charles had taken the helm during the passage to Jersey and it is said that the two early experiences of seamanship led to his lifelong passion for the sea. In Jersey Charles was able to set up his court at Elizabeth Castle and once again to experience the trappings of royal life. During his stay in the island there were many celebrations, including military reviews, church services, bonfires and various entertainments.10 The King after fleeing from Oxford was now being held by the Scots and in his letters was adamant that Charles should join his mother in France. This view was reinforced by the Queen when she wrote to her son ‘I must positively require you to give immediate obedience to his majesty’s, commands’.11 The Prince decided he must comply and sailed from Jersey on 25 June leaving the Kingdom for France.

Prince Charles remained in France and then Holland until in January 1649 his father King Charles I was tried and executed. The Prince was now declared King in Jersey and Scotland but in England Parliament had declared a Commonwealth. Despite an attempt to regain the throne of England Charles was defeated at the Battle of Worcester in September 1651 and was forced to escape once again to France. He remained in Europe mainly in Holland until in 1660 the monarchy was restored and he returned to England as King Charles II.

Linda Batchelor

Bartlett Maritime Research Centre and Library, National Maritime Museum Cornwall

August 2020

- Nine children were born to Queen Henrietta Maria and King Charles I from 1629 to 1644. Six of these children were living in 1644. Charles born prematurely and died May 1629, Charles b May 1630, Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall, later King Charles II, Mary b November 1631 Princess of Orange, James b October 1633, Duke of York, later King James II, Elizabeth b December 1635, Ann b March 1637 d December 1640, Catherine b/d January 1639, Henry b July 1640 Duke of Gloucester, Henrietta Anne b June 1644.

- Green Letters of Henrietta Maria Charles to Mayerne May 1644

- Henrietta Anne was left by the Queen at her birthplace Bedford House, Exeter, with the Queen’s lady in waiting. Lady Dalkeith. Lady Dalkeith was married to Robert Douglas, eldest son of the Earl of Morton. She was known for her courage and her loyalty to the crown and accompanied the Queen to Exeter from the court at Oxford. The Queen had taken refuge in Exeter in order to give birth to her daughter who was born there on 16 June 1644 but left soon after the birth to escape the advancing Parliamentary forces. Lady Dalkeith became godmother to the Princess Henrietta in Exeter Cathedral on 21 July and the King was able to meet his new daughter when his army reached the city on 26 July. He stayed only for a brief period and left Henrietta there with Lady Dalkeith. The city then came under siege from the Parliamentary army until the Royalist surrender in April 1646. Lady Dalkeith was allowed to leave with the Princess and they were given safe conduct to Oatlands a royal residence in Surrey but were then ordered by the Parliamentary authorities to join the household of the King’s other two children at St James’ in London. However Lady Dalkeith posed as a Frenchwoman, assisted by a French servant as her husband, and escaped with the Princess dressed as a boy. They walked to Dover carrying the Princess who told people they encountered that she was not a boy and was not used to being so shabbily dressed. Despite this they were able to board a French packet ship for Calais and take the Princess, her mother’s ‘enfante de benediction’ to the Queen, at St Germaine. Lady Dalkeith remained with the Queen in France until the death of her husband in 1651 when she returned to England but died there suddenly in 1654. The Princess Henrietta Anne, ‘Minette ‘ grew up in France and married the brother of Louis XIV. Her brother Charles II was restored to the throne of England in 1660. Charles described her as an ‘Exeter woman’ and gave the city a full length portrait of his sister, still with the city today, to commemorate the part they had played in her life.

- CSPD Charles I 1644 Henry Jermyn to George Digby

- CSPD 1644 11 July Letter Earl of Warwick to the Commonwealth of Both Kingdoms

- CSPD 1644 17 July Letter Earl of Warwick to the Commonwealth of Both Kingdoms

- At the outset of the war Mary, betrothed to the Prince of Orange, was in Holland. Charles and James were with their father at Nottingham and subsequently at Oxford. The two younger children, Elizabeth and Henry were at St James’ in London taken into the ‘care and control’ of Parliament. Charles escaped from Cornwall to France via the Isles of Scilly and Jersey on 2 March 1646. James after capture by the Parliamentary forces when Oxford fell was taken to join Elizabeth and Henry at St James’ and escaped from there to Holland in April 1648. Elizabeth and Henry saw their father while he was in captivity at Windsor and Hampton Court and shortly before his execution in January 1649. In 1650 they were taken to Carisbrooke Castle, Isle of Wight, where Elizabeth died in September 1650. Henry remained there in captivity until he was released ‘to go out of the realm’ to Holland in 1653.

- Memoirs of Lady Ann Fanshawe

- Sources for Pendennis Castle English Heritage.org.uk

- Societe Jersaise The Journal of Jean Chevalier 1642-1651

- Green Letters of Henrietta Maria Henrietta Maria to Prince Charles 20 June 1646