The Falmouth letters

23 April 2024The Spanish letters

23 April 2024Our research into the authorship of the Ceuta Papers led us to a set of letters written by Captain Charles Adam of the frigate HMS Resistance 38. He was the officer who commandeered our putative author, Joseph Humphries as his purser.

The letters give an insight into the comings and goings in the port of Falmouth between November 1808 to February 1809, the early and tricky stages of the Peninsular War, and shine a light on the logistics of Navy in supporting land armies.

Just turned 27 years of age, Charles Adam had had an impressive career and had seen action in several parts of the world. There is a full biography at the More than Nelson website.

As a Scot by birth with an Admiral as an uncle, he was clearly a determined man. No one harmed their career by sending regular updates to their boss and Charles used his relatively freedom from fleet control to make his mark with the Admiralty, specifically with the Honourable William Wellesley-Pole, the Chief Secretary to the Admiralty. Despite the name, Wellesley-Pole was a younger brother of Richard Wellesley, an older brother of Arthur and Henry who we meet in the Ceuta Papers as an ambassador arriving in Cadiz. By the end of 1809, Richard was Foreign Secretary and a Marquis, Arthur was commanding British troops in Portugal and a Viscount and William (now Lord Mornington) would be Chief Secretary for Ireland. It was quite a family.

At the beginning of 1808, Resistance was engaged in escorting convoys of troops to and from the Peninsula. It is perhaps a measure of the impact of the Battle of Trafalgar three years earlier that such convoys required little more than a frigate to sail across the face of the French navy which was bottled by the dominant Royal Navy.

In July 1808 Charles had escorted a convoy of troops from Cork to the Peninsula, quite probably General Wellesley’s troops for the battles of Rolica and Vimiero (see Historical Background) which were fought in August.

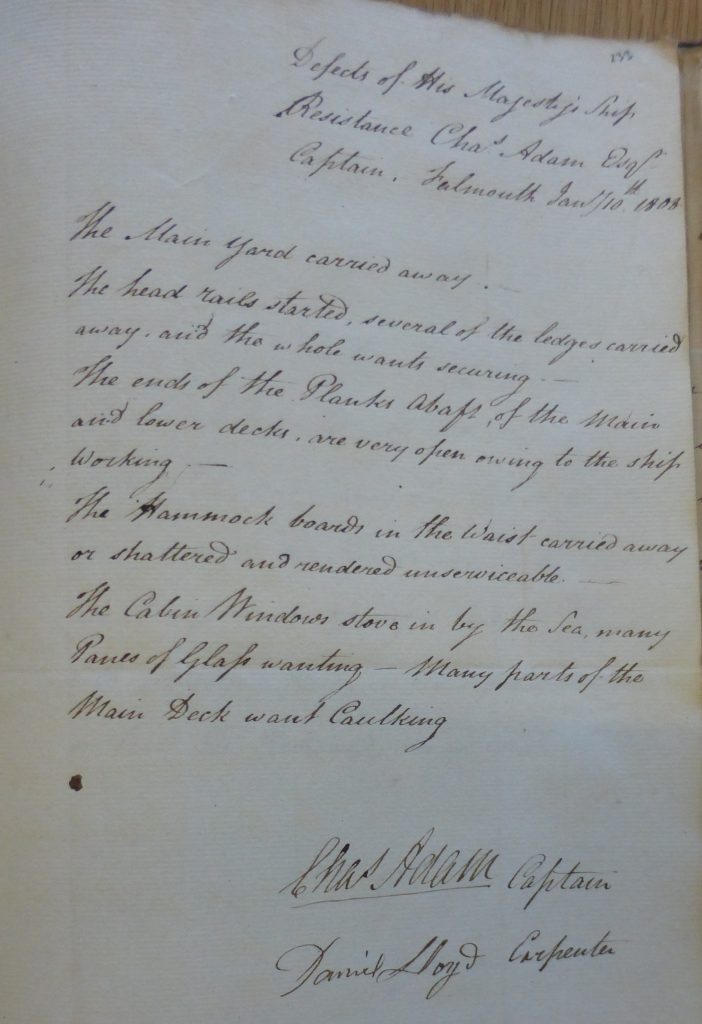

In the aftermath of the battle of Vimiero, Resistance escorted a convoy re-patriating the Second Division of Junot’s defeated French forces to Quiberon Bay. The weather was against him. He managed to unload the troops but then struggled to reach Falmouth with a dozen of the Transports. This was a cue for a spate of letters describing the situation.

He briefly reported to Spithead but was sent back to Falmouth which was being used as something of a port of refuge for Transports from the Peninsula. It appears that the Admiralty was pleased to have an experienced officer in Falmouth, able to sort things out.

But another convoy was in the offing and Charles was keen to join it and take it back to the Peninsula. Again, the weather had other ideas and it was not until February that he was able to set sail, with a new purser on board, Joseph Humphries, our possible author.

There is a short break in the correspondence until March 1809 when he turns up off the Spanish North coast, liaising with the Spanish troops in the Asturias. Although not directly related to Falmouth, Joseph Humphries would have been on board at the time and the letters are included here.

Several things are striking about these letters to modern eyes. The slowness of communication is marked. We are so accustomed to instant communication that it is hard to imagine how the Admiralty made sense of the many bits of information coming in from different captains in different parts of the world, all operating on different timescales.

Then there is the volume of correspondence. The British Navy was large and if every senior captain was writing on an almost daily basis then the postmen and secretaries would have been very busy filtering the letters for information. Disentangling the truth from the fog of war must have taken a large number of people and great skill. Did they have the equivalent of the WWII ‘plotting room’ with WRNS pushing blocks of wood around a table to indicate the location of their ships?

And then there is the amazing feat of assembling convoys of up to a hundred ships to transport and supply large armies in the field. Somehow, Lord Gambier (we assume) and his team off Spain conjured up enough Transports to re-patriate the French troops in October 1808 and then, possibly from a standing start, find another fleet to evacuate the remnants of General Moore’s army from Corunna in January 1809. If that were not enough, convoys were going back to Portugal and to the West Indies while all this was going on.

And what happened in Falmouth when 30 ships full of troops suddenly arrived after Corunna: how were they fed and watered and where were they housed when they finally reached Portsmouth?

A simple line like ‘The British sent an army to Portugal’ to support the king’ in a history book clearly disguises a Herculean effort.

In many ways, the correspondence asks many questions about the logistics of the day but it obviously worked, and worked well.