Fiona, the Fifes and the Marquis of Ailsa

28 July 2018The Early Years and the Fifes

28 July 2018Leaving for a moment the history of the Fifes of Fairlie, let us look at another type of the old Scottish yachtsmen whose patronage assured the success of Clyde yachting. Dr. John Cairnie, of Curling Hall, Largs, owner of the 17-ton cutter Nancy, was one of the best remembered of the early worthies of the Royal Northern. As fine a curler as he was a yachtsman, this Dr. Cairnie was a typical all-the-year-round sportsman, with unlimited enthusiasm and no mean skill on the rink or on the sea. The dovetailing of his two great sports is of itself interesting. It was Dr. Cairnie who founded the Royal Caledonian Curling Club, and he also introduced the game into Ireland and invented the artificial curling pond. Although so keen a curler, he could not have his yacht out of sight even in winter, and, to solve the problem, he had her drawn up on a cradle close by his curling rink, and as she sat there he entertained his curling guests on board. The little boat would also carry the granite blocks from Ailsa Craig which were to be hewn into stones for the ‘Roarin’ Game.’

About 1830 the success of Mr. Robert Sinclair’s Clarence brought about many alterations in the models of existing yachts, and, among others, Dr. Cairnie’s Nancy was lengthened. William Fife did the work, and, so that the doctor should not lose sight of his beloved little ship for so long a period, the alteration was carried out at Curling Hall. During the progress of the work the second William Fife, then a mite of a child, carried his father’s dinner over the three miles which separated the Nancy’s home from the yard at Fairlie.

In a work which Dr. Cairnie wrote on curling, the following passage occurs: ‘We have what we call picnic dinners, where every curler provides his own dish, and brings the drink he likes best. We, last season (1832), had four of these picnics, and the scene of festivity was on board of our cutter, lying high and dry on her carriage by the seaside. The first dinner this season was on November 5, and called forth the thunder of our artillery when the toast appropriate to the day and those connected with curling were given from the chair.’

Against the famous Clarence the doctor backed a friend to sail the Nancy around the Greater Cumbrae. So worthy was the friend that, to within a mile, there was ‘nothing in it’ between the two yachts. At that point, however, the wind died away, and both yachts drifted about with empty canvas. A gentle air of wind which played about the flag-boat kept a tantalizing distance from the yachts, until Blair, the skipper of the Clarence, with Mahomet–like philosophy, decided to try to get his yacht within its sphere of influence. Presumably to sluice down the decks, he ordered his men to get the buckets out, and so well were they handled that the Clarence gradually worked into the breeze before the trusting amateur was alive to the tactics of his opponent. The Nancy was a beaten boat, and, as yacht-racing in those early days would seem to have been on the same footing with love and war, we hear nothing more of the race. Dr. Cairnie, yachtsman and curler, died in 1842, and for him the following Burns-like lament was written:

‘Why drops the banner half-mast high,

And curlers heave the bitter sigh?

Why throughout Largs the tearful eye

Looks bleared and red?

Oh, listen to the poor man’s cry,

John Cairnie’s dead!’

Before leaving this interesting old yachtsman, a matter which brought him into considerable notoriety may be mentioned. The Scottish Sabbath of to-day is often cited as a model of strict observance, but that of seventy years ago was one of Puritanical strictness and severity. Sunday sailing in Scotland is still a controversial point, and on the Day of Rest many Clyde yachts never leave their moorings. It may easily be imagined, therefore, that the setting out of Dr. Cairnie occasionally on a Sunday did not pass without remark. Even among his retainers the practice was denounced, and one of them, Tom Dyer, who would appear to have acted in the dual capacity of gardener at Curling Hall and forward hand on board the Nancy, read him a most effective lesson on the point. The doctor and Dyer were trying one Sunday to work the Nancy round the Farland Point in a calm. Ultimately it seemed as if the boat must be washed on to the rocks by a strong tide. Getting alarmed, the doctor ordered Dyer to get the dinghey ahead and tow the Nancy to a safe offing. This was just the sort of chance Dyer had been waiting for to put in a shot against the hated Sunday sailing, so, settling down on the bitts, and proceeding quietly to fill and light his pipe, he said calmly: ‘I’ll tow the cutter nane. If she gangs ashore, she can jist di ‘t. It’ll only be a judgment on you for your Sunday sailing. As I’m not a free agent in the matter, the Lord’ll tak care o’ me, an’ you can shift for yoursel’.’ The doctor, who had only one hand, the other having been destroyed by the bursting of a powder-flask, could do little about a boat but steer ; so, after a little heated argument, he compromised the matter by assuring Dyer if he would tow the boat to a place of safety, he at least would not be asked to go sailing any more on Sunday. That being just what Dyer wanted, he soon had the Nancy out of danger.

The rapidly increasing popularity of yachting on the Clyde brought several excellent skippers to the front. Among the more prominent of these early masters were Blair, McKirdy, and Matthew Houston, of Largs ; the Whites of Gourock ; the Cochranes and Barrs of Cardross ; and William Jamieson, of Fairlie.

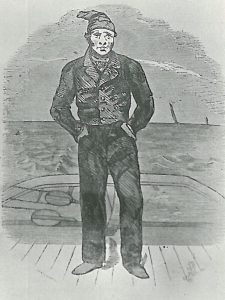

Robert McKirdy. First of the Clyde Racing Skippers. Reproduced from a sketch in Hunt’s Yachting Magazine.

Unfortunately, none of these early Clyde yachtsmen had a chance of trying their skill against their English confreres, and although Mr. Rowan, of Glasgow, was anxious to match McKirdy, his own skipper, in his 53-ton cutter Cymba, against Nicholls, the then crack English skipper, on any English yacht, for £500 a side, the match was never sailed. Strange to say, it fell through on account of McKirdy’s objection to be interested in what he considered a gambling transaction, and, as he said, being put up ‘like twa cocks in a pit.’ His attitude was respected by Mr. Rowan and by Nicholls himself. As Nicholls would have steered the Mosquito, however, it is much to be deplored that McKirdy’s conscientious scruples were not appeased.

Strange to say, Blair of Campbeltown was a tailor by profession. Employed by Major Morris, of Moorburn, as ‘orra’ man, Blair soon found himself on the yacht of that early Clyde Corinthian, and so quickly did he learn the art of sailing that he was made master of one of the famous Clyde ‘Ranterpikes’- three-masted fore-and-aft schooners which were displaced by steam in the Clyde and Mersey carrying trade. Here was a school to bring out the best qualities of any sailor, and the quondam Campbeltown tailor and Largs yachtsman soon became one of the most famous passage-makers in the trade. There was a strange custom among the owners of these traders that they gave a new hat to the skipper for every spar he carried away. Billy Blair was said to have had the finest collection of headgear of all the skippers of Scotland. In his later years Blair plied the ferry at Loch Ranza, where, by the capsizing of his boat, he was immersed for several hours, from which he never quite recovered.

McKirdy sailed Stella and Cymba, the two best of the early boats of the second William Fife, who generously testified to his skill.

For fifty years the second William Fife worked at his profession, following an ideal which he set himself early in his career. To make money, if possible, was his desire, but to design and build beautiful yachts was his ambition and great aim in life. In the former wish he was greatly disappointed for the greater part of his time, but the singleness of purpose with which he followed the dictates of his artistic temperament assured success in the latter. He sacrificed nothing to his artistic nature, and even when sorely in need of concluding a bargain he stood firm for his principles. Of this part of his nature the following incident bears striking testimony: A schooner which he had built ‘on spec.’ was long in finding a purchaser. In a time of pressing need one arrived who undertook to buy the vessel provided she was fitted with bulwarks 3 feet high. Ruefully, Mr. Fife had to decline the offer, and firmly refused to sacrifice the appearance of the boat even for the much-needed cheque. With a dry little laugh he said: ‘’I hae kept her a fang while, but I’ll keep her a while yet raither than mak’ a common cairt o’ her at the feenish.’ Fortunately, the would-be purchaser subsequently returned, and a compromise satisfactory to both parties was effected.

The fact that this member of the Fife family left much of his work to be done on his yacht in frame gave rise to the belief that he was a ‘rule-of-thumb’ worker, and trusted to his marvellous eye rather than to careful planning. This, however, was not so, for, like his son, he was a clever draughtsman. To-day there are designers who prefer to have some latitude when the model takes form, and Fife’s perfecting of the model as the building of the boat proceeded was part of a carefully-thought-out system. Like his father, he was interested in all the scientific research in connection with his art, and he added the experience of practice to the sometimes unworkable suggestions of the theorist.

It was only late in life that the second Fife played the role of designer only, but with such skill did he do so that he finally refuted the argument that he was merely a builder.

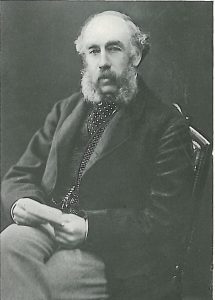

Dr. H. M. Lang. First Clyde yachtsman to win a Royal Cup. Patron of William Fife II.

The fortunes of the Fairlie yacht-building firm turned with the building of the 35-ton cutter Stella for Dr. Hugh Morris Lang, of Blackdale, Largs, a gentleman of independent fortune. Dr. Lang was a medical man by profession, and a banker by inclination. He became a firm friend of Mr. Fife, and his expert advice enabled the yacht-builder to put his business on a firm financial basis.

The Stella was built in 1848, but the addition of 6 feet to her fore-body three years later made her one of the finest windward cutters of her day. She was, however, no more remarkable than her skipper, Robert McKirdy. McKirdy was a hand-loom weaver by profession, and, like the majority of the followers of that now almost extinct craft, he was a most reserved and thoughtful man. He had few equals afloat. In the Stella he won two Queen’s Cups in 1852, one at the Royal Irish and the other at the Royal Cork Regatta.

The Queenstown match of 1852 was a memorable one. Two prizes were offered—a Queen’s Cup and an Exhibition Cup, the latter in celebration of the famous Exhibition in London. Several of the yachts were entered for both cups, and it was decided that one gun should serve for the starting of the double event. Thirteen vessels in all competed.

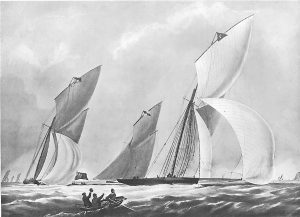

Cynthia, Cutter, 50 tons. Built in April 1849 by Messrs. Wanhill of Poole. Also showing Mosquito and Heroine.

The start was from anchors with headsails down, and the first few miles would be to windward under the existing conditions. Lots were drawn for positions, and Stella got thirteenth place, or to leeward of the entire fleet. This bad luck so affected Dr. Lang that he agreed with his guests—among whom was William Fife—that the position was hopeless. Before ordering his yacht out of the race, however, he decided to consult his skipper. McKirdy, usually so economical of speech, was astounded. ‘No start !’ he cried. ‘We’ll no be lang under the lee o’ some o’ that lot.’ That settled the matter, and the Stella started. Mr. Roe’s Cynthia was the favourite, and with Starkey, her Irish captain, in charge, she was a likely boat. So far to windward was she, however, that it was not till they had reached the weather-mark that McKirdy, having gradually worked yacht after yacht out of position, shot his fine cutter on Cynthia’s weather and rounded the mark abreast of her, practically assuring the cup for Dr. Lang. The skill with which the Stella was brought into the coveted position commanded the admiration of all, and is still remembered as a masterpiece of sailing.

So confident was Fife that he could beat Stella that he laid down a 53-ton cutter without being commissioned. When in frame she was seen by Mr. J. M. Rowan of Glasgow, and so impressed was he with her good looks that he immediately set about disposing of his yacht the Aquila, that he might purchase Fife’s latest design. He succeeded in both, and Cymba, the new yacht, became his. Although sailed in 1853, it was not until the following year that she was finished and entered upon her racing career in charge of McKirdy. Cymba was the first of Fife’s yachts to have lead ballast on her keel, and she had also wire rigging, then a novelty on the Clyde. Speaking of the Cymba, a critic of her day writes: ‘She has proved herself a splendid sea boat in very heavy weather, and unites the properties of great speed and seaworthiness to a greater extent than probably any other vessel afloat. She is likewise one of the most elegantly fitted and appointed vessels of her day, and reflects the greatest credit upon her spirited owner, under whose vigilant eye she was built and fitted.’

Opening her racing career at Kingstown in 1854, the Cymba won the chief prize of the Royal St. George’s Club and a hundred-guinea prize given by the Royal Irish Yacht Club. In the same season the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland gave a Grand Corinthian Plate for a race in which the yachts were to be handled entirely by amateurs. These amateurs were to be also members of Royal clubs, and the professional skippers were only allowed on board as ‘advisers in chief.’ Seventeen amateurs assisted Mr. Rowan in his famous cutter, and so well did they manage in the prevailing heavy weather that she won handsomely. On her return to the Clyde success continued to be with Mr. Rowan and his fine boat, but at the close of the season he decided, on Mr. Fife’s advice, to have her lengthened by the bow, and the work was carried out at Ardrossan under her designer’s supervision.

Unfortunately her skipper was never to sail again in the famous yacht. On a cholera epidemic breaking out in Largs, he was seized by it and died on October 12. As McKirdy was born in 1803, his loss to yachting was premature. Besides the boats enumerated McKirdy successfully sailed several others. One of them, Mr. Thomas Douglas’s 30-ton Meteor, was built at Ardrossan by a cousin of William Fife. A rather amusing incident is told in connection with McKirdy and the Meteor. Mr. Douglas, who lived where the Royal Northern Yacht Club-house now stands at Rothesay, had arranged to take part in the Irish regattas, but pressure of business altering his arrangements, he gave orders for the Meteor to be kept at her moorings. McKirdy’s grief was none the less deep for being unspoken, and the loss of an Irish cup upon which both he and his master had set their hearts was greatly to be deplored. Without a hint of his intentions to his master he got the Meteor under way, and under cover of the darkness laid his course for Dublin Bay, where he found a willing qualifier and a handsome cup. Mr. Douglas’s wrath was soon overcome by his admiration of the enthusiasm which prompted the act of disobedience, and both McKirdy and the cup were welcomed on their return to Rothesay.

Another amusing incident in the Meteor’s career is worthy of record. Racing Meteor at Largs against an Irish-owned yacht named the Charlotte, after establishing a useful lead in half a gale of wind, the crew of the Meteor were astonished to find that the Mount Stuart mark-boat had disappeared. McKirdy’s advice was to put about where the mark-boat ought to have been and continue the race. His advice was taken by Mr. Douglas, but the example was not followed by the Charlotte, the crew of which searched for the missing boat, which they presently discovered high and dry on the Little Cumbrae. Here was a problem! Robert Wright, their pilot, was a long-headed Largs man, and they looked to him for advice. His advice was to sail round the island, as no other method of making the mark was feasible. Entering into the humour of the occasion, the Irishmen took the advice and, although arriving long after the Meteor, the prize. There was no Court of Appeal, and Mr. Douglas was so incensed with the decision of the Racing Committee that he cut the club buttons from his coat. The crew of the Charlotte were, on the other hand, so delighted with the result of the match that they went ashore and overtaxed the wine cellar of the White Hart Hotel at Largs, then the unofficial club-house of the Royal Northern Yacht Club. Mr. Douglas was a good sportsman, however, and before the close of the season the breach was made good.

In spite of McKirdy’s conscientious objection to being pitted against John Nicholls for a wager, the excitement of a race once made an actual punter of him. In this particular race the Meteor’s chief opponent was a famous English yacht which was strongly fancied for that and many other races. The yachts started down the wind, and, as that was the visitor’s best point of sailing, she quickly left the Meteor. So quickly, indeed, did she get away that Mr. Graham, a nephew of Mr. Douglas, who was in charge, exclaimed: ‘I’m very sorry I gave my consent to the Meteor being started in this race. We’ve no chance—no chance whatever. Why, it’s ten to one against us already!’ After hearing this pessimistic opinion several times repeated, McKirdy put the tiller between his legs, and, fishing beneath his jersey, produced a herring-scale bespangled pocket-book. From this he produced a pound note, and, with a confidence that acted like a tonic on the crew, said, ‘If you’re still o’ the opinion, cover that.’ Mr. Graham took the bet and the hint. On coming on the wind the crew worked with a will, and McKirdy put some of his best work into the handling of his charge. So well did he manage that, within a hundred yards of the flagship, he put the Meteor ahead of his English rival. Before the echo of the gun had died away Mr. Graham thrust two five-pound notes into the skipper’s hand, and, taking from his pocket a valuable gold watch and chain, he hung it round his neck, saying the while, ‘Wear that, McKirdy, in memory of as good a race as you ever sailed – of as good a race as I ever expect to see any man sailing.’

In those early days a skipper’s wages were £1 per week, with neither clothes nor prize money, and the ordinary hands got 16s. to 18s.

The alterations to the Cymba were carried out as arranged, and McKirdy’s place was taken by William Jamieson, of Fairlie, a cousin of William Fife. In his hands the cutter maintained her reputation, and the finish of 1855 found her undefeated. In her second year one of Cymba’s finest races was sailed at the first big regatta held at the Isle of Man. The meeting was an historical one, and Cymba’s race worthy of it. Cymba won easily from Glance, 35 tons, Foam, 25 tons, and Coralie, 35 tons.

When Cymba was the pride of the Clyde the Earl of Eglington was the popular Commodore of the Royal Northern. As the conceiver of the memorable Eglington Tournament, this wonderful sportsman will always be remembered. Although Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and one of the most polished speakers of his day, he was a sportsman passionately devoted to sport in every shape and form. For the Royal Northern Regatta of 1855 Lord Eglington presented a valuable pair of vases to be sailed for by yachts over 10 tons, the time allowance being limited to 30 seconds per ton up to 50 tons, and 15 seconds beyond. In a gale of wind the following seven yachts started:

Gauntlet, 66 tons- Mr. Houldsworth (Vice-Commodore Northern Yacht Club)

Cymba, 54 tons- Mr. J. M. Rowan

Stella, 41 tons- Mr. J. Steele

Coralie, 35 tons- Mr. H. E. Byrne

Blue Bell, 31 tons – Mr. R. N. Grinnall

Foam, 25 tons- Major Longfield

Onda, 20 tons- Mr. R. W. Laurie

The yachts took five minutes to get off, Gauntlet leading, Onda last. One by one the competitors had enough of it. Only three finished, and Cymba won the match easily. It was her race, and the dry windward work she made under the trying circumstances was reckoned as one of her best performances. So fierce was the gale blowing throughout the day of the race that Lord Eglington was unable to drive to Largs until late in the afternoon, when the weather was too rough for him to reach the committee boat.

Evadne was the first of several fine yachts built by Fife for Mr. Couper – the Surge in 1858, Æolus in 1861, and the Surf in 1863. These boats were of great length in comparison with the accepted proportions of the time, their proportion of beams in length being 4.3, 4.7, and 4.5.

In the hands of an English skipper named Tim Walker, who had done much good work on Mr. Grove’s cutter Mosquito, Mr. Couper won a Queen’s prize in Aeolus in 1862, and one in the Surf in 1863. Walker was the first English skipper to migrate to Scotland. He died at Gourock in 1886.

At the close of the season of 1855 Cymba was purchased from Mr. Rowan by Mr. Thomas (now Lord) Brassey. So fine a reputation had the boat that the purchase price paid by Lord Brassey (£1,750) was exactly Fife’s building estimate.

Although Cymba never rounded Land’s End, she defeated the 35-tonner Glance, built by Dan Hatcher at Southampton, a boat which was considered one of the best of her time.

To replace Cymba Mr. Rowan had the 80-tonner Oithona built for him at Fairlie. Jamieson transferred his services to the new boat, which did much good work.

William Jamieson was, during his long career, associated with many historic yachts. One of these was Fidelio, a composite yawl of about 110 tons. She was designed by Mr. Tennant, a partner in the Glasgow chemical business bearing that name, and the model, cut from a bar of soap, showed a powerful and shapely vessel for her day. In construction she was an improvement upon the composite vessels built on the Clyde. She was framed up at Port Dundas, and finally put together in the yard of Mr. Hill at Port Glasgow, a yard which became famous for many notable yachts, including the 10-tonners Merle and Florence, and the 20-tonner Sayonara. The Fidelio was built with nine iron frames set upon the keel, and kept in position by an iron stringer. These frames were sheathed with strong planking laid on diagonally, and another layer placed fore and aft.

It has been generally understood that composite construction in yachts, so far as the Clyde is concerned, originated with Messrs. Steele, of Greenock, in the schooners Selene and Myanza, and the cutters Oimara and Garrion, in the sixties, as a result of the success of such construction in the tea clippers. There were, however, earlier attempts to combine wood and iron, for in or about the year 1842 the Cyclops, a 30-ton cutter, was built in a Clyde yard with an iron under-water body and topsides of wood.

Fidelio was built with a view to winter cruising abroad, and her owner, wishing to discover by actual experiment her suitability for this purpose, engaged Jamieson to take her from Troon to Lisbon with a cargo of iron ore, and to bring back a cargo of fruit. After several voyages Jamieson’s reports as to the performances of the boat were so favourable that Mr. Tennant had her fitted as a yacht, and Fidelio left the Clyde with her owner on board for a foreign cruise. Mr. Tennant, whose health had given cause for anxiety, greatly benefited from this cruise, but in the spring, when returning home, a fierce gale was encountered, which lasted for several days, and at Holyhead Mr. Tennant was taken ashore in a precarious condition.

Jamieson, as a middle-aged man, sailed the Fiery Cross, owned by Mr. J. Stirling, a Dumbartonshire yachtsman. Fiery Cross was one of the second William Fife’s best schooners, and in sailing her Jamieson displayed great skill and courage. One of his famous races took place in 1864, the year after the boat was built. It was a match from Liverpool to Kingstown, and Fiery Cross met the English clippers Albertine, Madcap, and Mosquito. Bad weather was encountered, in which Fiery Cross received a severe dusting, but Jamieson drove the boat through in spite of the fact that she was shipping large quantities of water. At the height of the storm John McNee, the old steward, who was always being torn between his admiration for Jamieson’s courage and daring and his desire to get through the world in comfort, after trying in vain to keep himself dry in his hammock, donned his oilskins and sea boots, and went back to bed with an amusing resignation, muttering as he did so, ‘Oh, Lord, he’s at it again, and we’re in for another nicht o’t. Ah, weel, there’s nae harm in being prepared for the worst.’

Jamieson was over eighty when he died. Though a great skipper, he was scarcely equal to McKirdy, a fact which he himself was forced to appreciate.

William Fife (the second) had by this time secured a few of the best Scottish yachtsmen as patrons. These included the Messrs. Finlay, of Glasgow, Mr. Emanuel Boutcher, the Marquis of Ailsa, Mr. H. B. Stewart, of Glasgow, Mr. R. K. Holmes-Kerr, of Largs, and Mr. David Richardson, of Greenock. For all these yachtsmen Fife built first-class boats, many of which became famous racers. Dr. D. W. and Mr. Alexander Finlay, of Glasgow, were his most progressive patrons. He built for them the cutter Cinderella, 15 tons, in 1862 ; the Torch, 15 tons, in 1865; and the cutter Kilmeny, 30 tons, in 1866. All these were fast, and the most successful of the smaller-sized boats which he had so far built. Their owners had ideas as to modelling and building, and Fife was compelled to adopt many of these against his will. In the building of Torch they enforced their demands for lighter scantlings, and in place of 13/8 inch planking, planking of ¼ inch less thickness was used. Upon their suggestion, also, the frames were hewn and steamed alternately. Fife complained that these scantlings would produce a basket-like hull, and at first refused to build to them, on the ground that the boat would not hold together for more than two years. However, he pocketed his prejudice, and the Torch was built, and for many years was a champion prize-winner.

Cinderella was one of the first, if not the first, Clyde yacht to sport a topsail with jackyard. The jackyard itself was small, but the topsail was a large one. As far as is known, hollow spars were also introduced to the Clyde on the Cinderella, a hollow gaff being the idea of Mr. Alexander Finlay. The hollowing was accomplished by splitting the spar and gouging out the centre, after which the halves were fixed together. The experiment was not successful, and the spar was discarded after a brief trial, owing to its instability. It is also believed that Cinderella was fitted with a hollow topsail yard, hollowed in the same manner as the gaff, and strengthened by battens of greenheart lashed in the vicinity of the slings.

Cinderella as a racing craft is not so well remembered as Torch and Kilmeny, though she won a number of exciting races. She began her racing career on the Mersey, being opposed by the afterwards celebrated Mersey 10-tonner Vision, then newly launched.

At one period of the race the Fairlie boat had a long lead, but the finish, a stiff turn to windward over a strong adverse tide, found her at a disadvantage. Alexander Wilson, Messrs. Finlay’s skipper, finding that the Vision was being taken over an easier course, and learning that the pilot of the Cinderella was father of the pilot of the Vision, luffed his boat away in beside the Vision, and quickly gained the weather berth. The move was not too late, and an exciting finish gave the victory to Cinderella by a single second.

In crossing from Liverpool to Dublin Bay Cinderella revealed a defect in planking, and it was with difficulty that she was got to Kingstown. Here, however, she was quickly repaired, and sailed excellent matches against the Vision and the Glide, the latter a new boat built by Mr. David Fulton. In one of those matches Cinderella and Glide became surrounded near the mark-boat by a crowd of the smaller-class racers, and the crush at the finish promised to be lively. Wilson, the skipper, anticipated the problem which, with a dozen bowsprits darting over the line simultaneously, the judges would have to deal, and placed a man at the bowsprit end, and the Cinderella won by two or three seconds. At Rothesay, too, this boat was associated with a close finish after a day’s remarkably close sailing. She was matched against the Swallow, a fast 18-ton cutter, owned by Mr. D. J. Penney, of Glasgow, and built at Poole by Wanhill, and the Harriet, 12 tons, built at Rothesay by a cousin of Fife (II.). The latter boat was the property of Mr. Ogilvie, one of the old school of Clyde yachtsmen living at Rothesay. The Swallow was in charge of Archibald Wright, the afterwards famous Clyde skipper. Harriet at an early stage of the race carried away her topmast, and the match resolved itself into a duel between Cinderella and Swallow. Several times during the day these boats passed and repassed each other, and at the mark-boat Cinderella was exactly her own length ahead. Having, however, to concede a few seconds to Swallow, the latter boat won. Cinderella was sold to Professor Thorpe, and ended her career by becoming a wreck on the Hebrides.

The Swallow and the Vision were among the first English boats to visit the Clyde, and the former boat was the object of considerable interest to the Clyde builders, the founder of the Fairlie Yard being a keen student of her lines, as well as the late Mr. G. L. Watson. The Vision was bought by Mr. Morris Carswell in the early seventies, and brought to the Clyde. Mr. Carswell was then one of the most popular racing owners on the Clyde, and the population of Largs, where he resided, were as enthusiastic over the Vision as the owner himself; and at the beaching and launching operations on Fairlie Beach every man and boy ‘lent a hand’ as a duty to the owner and his boat.

The washing of the sails of early Clyde yachts was not uncommon, and when the Vision arrived on the Clyde from the Mersey her sails were so grimy that it was deemed necessary to wash them, rather than wait for a new suit. The operation was not a success, Mersey grime resisting the Clyde water, but it provided much amusement for the young talent of Largs, who carried water for the ablutions. Another Clyde yachtsman, Mr. Bamatyne, owner of the Midge, also washed the sails of his yacht. Being a fastidious gentleman, he was, on one occasion, annoyed by the prentice weavers of Largs bathing in the Broomfields Wharf, built by Dr. John Cairnie, and, collecting their clothing, deposited it in the sea. The boys were awarded a prompt revenge, for no sooner were the snowy-white sails of the Midge laid out to dry than they were collected and deposited in the sea.

When Vision became the property of Mr. Carswell, she was given a complete overhaul. Her cutaway forefoot aroused the scorn of the Largs yachtsmen and fishermen, for Mr. G. L. Watson had not yet introduced his revolutionary ideas as to rockered keels and cutaway forefoots. Their relative bearing upon speed was unknown, and it was freely predicted that a boat with a cutwater similar to that introduced in Vision could not possibly hang to windward. Accordingly the cutaway portion of the keel at the bow, cleverly and daringly introduced by her draughtsman, was filled up in the most approved style with a piece of hardwood firmly bolted. This did not, however, ruin the sailing qualities of the Vision, and she won many matches against the cracks of her day. Mr. Carswell was a good friend to Largs yachting, and was one of the founders of the Royal Largs Yacht Club.

Kilmeny made her first appearance at the Mersey Regatta of 1864, but she was in an unfinished state, and her crew consisted of the Fairlie carpenters who built her. These men were keen, but untrained. The first race was in a slashing breeze, in which the fleet beat out to the north-west lightship with housed topmasts and reefed mainsails. While turning to windward with the strong breeze Kilmeny led a strong class in good style, but when running home the wind fell light and her crew were at great disadvantage in setting canvas and shaking out the reefs of the mainsail, and she was beaten. The next day she led the fleet to windward, but had the misfortune to break the jaws of her gaff, which lost for her the race. From the Mersey she went on to Kingstown, and here she opened a series of remarkable victories, which continued almost without interruption till first the Foxhound and then the first of the 40-tonners were sailed against her.

Torch, on the other hand, was almost a failure in her first year, and gave no signs of being a successful boat. In her second season, however, she was almost invincible, being beaten only by the 20-tonner Luna at Kingstown. She was sold by the Messrs. Finlay to Mr. George B. Thomson, under, whose ownership she was a complete success. She was subsequently owned and raced by Mr. W. H. Williams, of Hull, and Mr. W. Sinclair. During her racing career she gained about 100 flags. Her chief measurements were: Length overall, 48 feet ; beam, 9 feet ; draught, forward, 3 feet 9 inches ; aft, 7 feet.

The Kilmeny passed into the hands of Mr. Pascoe French, one of the most famous amateur yachtsmen of his day. For him, too, she sailed many fine races. Mr. French died in 1893, at his home, Marino, Queenstown, at the age of seventy-eight. His last vessel of importance was the 40-tonner Gleam, which he sold in 1878. Like many of the cleverest yachtsmen, both Corinthian and professional, he retained a fondness for the sea, and in the summer before he died he was sailing small craft in Cork Harbour with some amount of the dash and skill for which he had been distinguished in his younger days. He was once described as the prince of helmsmen, and John Houston paid him a fine compliment when he said that he was the only Corinthian against whom he found it necessary to take off his coat to defeat. At the time of his death Mr. French was the senior member of the Royal Cork Yacht Club, having been enrolled in 1837.